What is the value of Block’s closed loop?

Limited impact on unit economics, but better offers could lift volume

Key insights in this post

Block’s is trying to “close the loop” between its 3M+ Square Sellers and 57M+ Cash App users via Cash App Pay

Today, intra-Block transactions account for ~6bps of US annual card spend (Cash App Debit purchases at Square Sellers)

Several other payments companies have closed loops, but the most successful is probably Starbucks

30%+ of Starbucks purchases are made through the App

Consumers are incented with “Stars” that redeem for free coffee

Stores reduce friction and lift volume

Acceptance costs are lower via the stored value payment method

Cash App Pay reduces acceptance costs but none of those savings accrue to Square Sellers and Pay shifts revenue from Cash App to Square

Square has flat rate pricing, so the Sellers are indifferent to payment method

Square sees a windfall versus debit since interchange and network fees are eliminated – but Cash App gets no revenue

Block can reward Cash App via inter-company transfers from Square

In general, Pay only improves Block’s unit economics by eliminating ~8¢ of network fees per transaction when Pay displaces Cash App Debit

Benefits rise substantially if Pay displaces 3rd party debit cards, but that requires better incentives from the “Boost” program

Boosts are merchant-funded, cash-back rewards when using a Cash App Debit Card or Cash App Pay

Boosts are not differentiated from the Cardlytics-driven offers that most bank debit cards provide

Block could differentiate Boosts by making them SKU-based, leveraging the Square POS:

SKU-level offers could tap CPG manufacturers’ promotional funding rather than merchant funding – making offers richer and more targeted

SKU-level offers may help Square Sellers drive foot traffic and manage inventory by incenting for specific purchases

Differentiated Boosts give Block advantages on both sides of the ecosystem

Cash App users get meaningful reasons to use Cash App Pay versus third-party debit cards

Square merchants have meaningful reasons to use Square POS versus other ISV offerings (e.g., Clover, Genius)

Afterpay has minimal value in the closed loop

It is already available at any NFC-enabled POS, not just Square POS

It’s high interchange consumes most of the MDR earned from Square Sellers

It displaces use of the Cash App debit cards in some situations

Conclusions:

“Closing the loop” alone will improve Block’s unit economics much while shifting revenue from Cash App to Square (before intra-company adjustments)

Only if Block can upgrade the Boost proposition, likely via SKU-based offers, can “closing the loop” drive volume on both sides of Block’s ecosystem

Introduction

I am a big admirer of Block. Cash App is the most successful Neobank and Square has been consistently innovative for almost 20 years. I covered one side or the other in many posts over the past year: here, here, here, here, here, here, here, and cameo appearances elsewhere.

The company made some announcements recently that improve Square’s functionality and push Cash App into more of a depository – and they haven’t even fully leveraged their bank charter yet. The connective tissue is intended to be Cash App Pay, a closed loop method for the 57M+ Cash App members to make purchases at the 3M+ Square merchants using their Cash App balances.

But can all this become a economically valuable closed loop? If so, where do the benefits come from? This post will address these questions.

What assets are in play?

The core components of the closed-loop would be Square to aggregate merchants (“Sellers” in Block-speak), Cash App to aggregate consumers, and AfterPay to provide consumer credit. These are not the only Block products, but they are core to the closed-loop strategy.

Block’s closed loop opportunity

A brief overview of each component is worth outlining:

Square

Square serves small merchants (“sellers”) up through chains. Of their 3M+ merchants, the bulk have historically been small:

They have tailored solutions for Retail, Restaurants, “Appointment-based” businesses (e.g. salons), and Invoice-based businesses (e.g. caterers)

They serve some chain retailers, mostly in QSR (e.g., Shake Shack)

They offer value-added services, in particular, merchant lending on the Cash Advance model

The biggest share of Sellers are small or mobile merchants. As many as 2M are in a long tail of micro-merchants (<$125K of annual TPV). That still leaves as many as 2M larger merchants but, includes chain locations that use a different services model.

Cash App

Cash App started as a P2P system, similar to Venmo. It evolved into more of a Neobank, similar to Chime. It remains a hybrid. It has:

57M P2P users of which …

27M have the Cash App debit card, of which …

2.7M get direct deposit into their Cash App account

As I pointed out in this post, the P2P function provides a marketing pipeline of prospects for the debit card and eventually the transaction account.

Cash App has diversified into lending products like EWA and Advances. A material revenue source is instant transfers from Cash App to the customer’s bank account.

AfterPay

AfterPay is a BNPL lender that Square acquired in 2022. It competes with Klarna & Affirm among others, primarily with a pay-in-four product. Cash App customer demographics overlap nicely with the core BNPL user base.

Afterpay can already serve any POS via integrations with Apple Pay and Google Pay. It does not need the closed loop to improve acceptance.

Cash App Pay

This is a QR-based payment method that draws from a Cash App balance to pay merchants. It uses the balance first, followed by a linked debit card. By “linked” they mean a debit card issued by some other entity, usually the consumer’s primary bank.

How big is the opportunity?

The starting point for Block is tiny relative to the ~$10.8T of 2024 US Card spend (debit, credit & prepaid):

2024 Square TPV was ~$228B or 2.1% of total card spend

2024 Cash App “inflows” were $286B or 2.6% of total card spend

The likelihood that a Cash App debit card transacts at a Square merchant therefore equals: 2.1% x 2.6% or 0.06%, otherwise known as ~6 basis points. This may overestimate the cross-over as not all Cash App inflows are spent on the Cash App debit card – some is sent out as P2Ps and some is left as a balance in Cash App. 2025 YTD TPVs are higher for both sides: 10% for Square and 8% for Cash App.

No doubt there are metro areas or even neighborhoods where share is much higher, but ~6bp is the in-scope national market size assuming all consumers use Cash App whenever they transact at a Square merchant. The hope is that Cash App Pay can raise all these metrics.

What is the economic advantage of closing the loop?

Closed loops or ecosystems are an aspiration for many companies. Amazon is the best example, with Prime incenting consumers to shop at Amazon marketplace which incents merchants to list there. Shopify is trying to develop a similar virtuous cycle with Shop Pay and the Shop App.

An ISV example would be Mindbody, an ISV for Salons and Spas; it acquired Class Pass to capture a consumer proposition. Class Pass drives consumers to unused appointments at those kinds of merchants. Since those slots would otherwise have gone to waste, distributing at a discount through Class Pass is profitable. This is similar to the “empty airline seat” problem. Class Pass allows Mindbody to drive volume to its merchants where competitors cannot, giving it a higher partnership value.

The Starbucks mobile app is the most famous of them all. 30%+ of Starbucks in-store transactions are paid for on their App, with both convenience and offers driving that engagement.

The consumer earns “stars” redeemable for free coffee while also getting more convenience through a streamlined checkout and mobile ordering

Starbucks reduces payments acceptance costs and while rewards redemptions have low marginal cost

Starbucks is the kind of closed-loop model that Block no-doubt aspires to. Cash App Pay could impact both unit economics and volume.

Closed loop unit economics

The key challenge is Square’s famous flat rate MDRs: Currently 2.6% + 15¢ regardless of card type. This was one of Square’s most disruptive innovations. Merchants love the transparency and almost the whole SMB acquiring industry has adopted the flat rate model.

The problem is the flat rate makes Debit the most profitable transaction, because interchange is so low.

70% of the time, Interchange (IC) is ~25¢ (capped at 22¢ + 5bps)

30% of the time, Retail IC (exempt) is 80bps + 15¢

The Cash App debit card gets the exempt rate.

Switching the transaction to a book transfer between Square and Cash App saves only the network fee to Visa or MasterCard; on debit, this is typically 13bps + 1.5¢. For the typical $50 debit transaction this works out to 8¢ of savings. That book transfer eliminates the interchange as well, but that comes out of Cash App’s pocket and into Square’s pocket – Block is neutral.

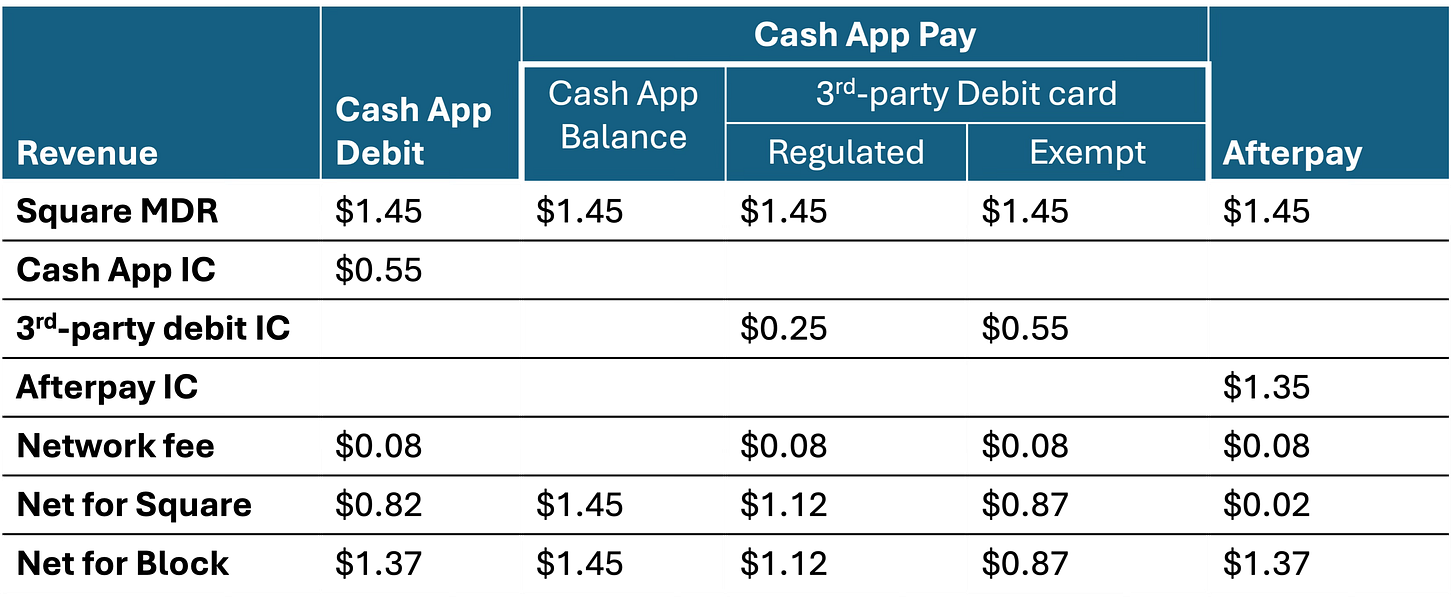

If the Cash App balance is insufficient, the transaction defaults to a third-party debit card. In that case, Cash App gets no revenue while Square pays the extra 8¢ in network fees – in other words, no change in economics for either side. The table below summarizes all this:

Block economics for a $50 transaction at a Square Retail client

(Square MDR at 2.6% + 15¢, Network Fee at 13bps + 1.5¢)

Note that Block does best if Cash App Pay displaces 3rd-party debit cards. Otherwise, Block is only slightly better off if Cash App Pay displaces Cash App Debit. In general, all proprietary methods merely redistribute revenue among the segments. For example, when paying with a balance, the table shows Square getting all the revenue, but Block could do an intracompany transfer to Cash App at any rate to reward that segment for the transaction.

The other consequence is that the merchant gets no benefit: that 2.6% + 15¢ is unchanged in every column. Cash App Pay works via QR codes, making it an exception process for cashiers, so why would merchants do it at all?

For larger merchants on IC+ pricing, paying with the Cash App Balance is an unknown. Square gets the same acquiring fee, usually under 5¢ per transaction; but, needs to negotiate a proprietary interchange rate for a Cash App Balance payment. This may be lower than the network IC rate, so Block may end up with reduced revenue.

Conclusions on unit economics

Closing the loop doesn’t accomplish much for unit economics. In general, it just shifts revenue from Square to Cash App or vice versa. The only real financial benefit is cutting out the networks when paying from a Cash App balance, but that is only worth 8¢ per transaction.

That means the lift would have to come from more volume, both volume new to the merchant and volume that shifts from third-party debit to a Cash App method. The next section will discuss that angle.

Closed loop volume impact

The closed loop could incent more Cash App users to transact at Square merchants using Cash App Debit or Cash App Pay. Demonstrably higher sales may get more merchants to choose Square over Clover, Genius and other ISVs — companies that do not have a consumer proposition.

Further, Cash App users, might put more of their spend through Cash App Pay or the debit card. Some might even switch their primary transaction account to Cash App.

So while the unit economics are not particularly compelling the volume lift may be. In other words, in the P x V equation, V is more important than P. This only happens if there is an incentive for consumers to use Cash App methods.

Cash App Pay usage incentives

What are the incentives? Cash App Debit and Cash App Pay offers instant discounts and cash back that appear to be merchant funded. The merchant pays Square the same flat rate on these transactions than they do for any other transaction. So the merchant has to believe that the consumer incentives will drive higher traffic to their store.

Most of these “Boosts”, seem similar to what most bank debit cards offer via Cardlytics. That means they don’t likely move the needle even in a paycheck-to-paycheck population.

Most offer programs, like Cardlytics, are at the Merchant level not the SKU level. SKU-level offers could be truly differentiating for this program. Getting to SKU level data requires deeper integration than merchant level discounts. But Square’s POS sees SKU on every transaction. That gives it advantages over other offers programs:

The merchant can set special offers by SKU. Those SKUs could be where the merchant has excess inventory, higher margins, or on SKUs known to drive foot traffic into the store (e.g., Milk). The merchant can tailor promotional spend to drive key outcomes

Cash App could get promotional money from CPG manufacturers. That means neither Block nor the merchant is funding the discount — traffic increases on the manufacturer’s dime. CPG promotional spending is a deep well that is otherwise difficult for small merchants to tap

If Boosts become more tailored they can drive real traffic. It would be hard to use Cash App Debit to drive this because the POS device doesn’t recognize it as Cash App until it is too late. But Cash App Pay uses QR which can be designed to recognize SKU.

The Cash App mobile app shows Boost-participating Square merchants but these may be locationally inconvenient unless the offers are rich enough. Where the consumer already shops at a Square merchant, the offers may cannibalize sales that didn’t require a Boost. And of course, the “optimizers” may come for the Boost but not stay for full-price purchases. These are common challenges for any offers program.

Conclusions on Cash App incentives

The Cash App incentives are not rich enough or regular enough to drive large numbers of Cash App users into Square merchants. There may be some geographies that have denser populations of each where it may be more effective.

Block likely needs to tap into Square SKU data to deliver offers for specific products. That might move Cash App users to frequent Square merchants. CPG’s might fund the offers for soda, snack foods, grocery staples and other common categories. To get the offers, users would have to use Cash App Pay rather than the debit card.

The current offers model won’t move the needle but an SKU-level model might.

What about Afterpay?

Afterpay POS economics depend on interchange. Online, Afterpay is usually integrated into a merchant’s purchase flow and earns a custom MDR; in most POS situations, Afterpay pushes a virtual card into Apple Pay or Google Pay so that the consumer can tap-and-go. Virtual Card interchange is higher than debit interchange, so Afterpay can cover its float cost while still charging 0% APR for the pay-in-4 loan.

That means Afterpay can already transact at almost any POS without any help from Cash App Pay. Since virtual card interchange is so high, Afterpay transactions are among the least profitable for Square. It is unclear to me whether Afterpay net revenue offsets lost Square margin. Of course, Block is better off if they do that transaction on Afterpay than on Klarna or Affirm.

Overall, Afterpay does not add value to the closed loop model.

Conclusions

Before writing this post, I took it as a given that closed loops offer better economics and higher volumes. There are good examples that support this assumption, especially Starbucks.

In other cases, closed loops did not deliver the goods. I lived through the relative failure of Chase Pay. Even JPM’s ~25% share of credit card spend and 20% share of acquiring wasn’t enough as it only touched ~5% of market transactions (20% x 25%). One challenge was low incentives and another was high friction (QR) compared to other mobile wallets (NFC).

In some cases, the closed-loop owner showed growth, but it isn’t clear that the closed loop was the reason. PayPal may be an example of this as their volumes kept rising even as their market position with small merchants deteriorated versus Shopify. Volume from smaller merchants (closed loop) at full margins shrank while volume from bigger merchants (wallet payment method) at narrow margins rose. Parent level economics deteriorated.

The closed loop opportunity starts from a small base (6bps of national spend). The key to growth is getting a critical mass on the consumer side to drive volume. Cash App has scale on the consumer side within a defined demographic, but Square’s footprint does not correspond to where those consumers are – there is overlap, but not concentration.

Driving Cash App customers to Square merchants requires an offers proposition that is better than those customers can get from their banks or elsewhere. As yet, Boosts don’t delivered this. Leveraging SKU data may be key to improving this, but that is not in evidence yet.

I conclude that placing much value on Block’s closed-loop economics may be wishful thinking until a better Boost proposition emerges.

Sorry for the delayed response. Busy weeks. The challenge with A2A payments is how Cash App gets paid. Visa & MC impose the Interchange prices on the entire merchant sector, but Cash App would have to negotiate deals one by one with every merchant. For Square merchants (mostly small), they Block already captures this, but they have small share, and none among the largest merchants. So while the technology would work and big merchants would happily take a zero cost payment, Cash App/Block wouldn't actually make much money. Cash App would be better off with their current strategy which is to make their debit card the primary card for more customers. They do that by getting more direct deposit relationships. The debit card has universal acceptance already and the price is set by the networks so Block gets universal acceptance at an attractive price with no effort.

Interesting as always. Curious to hear your thoughts on the feasibility of evolving Cash App Pay into a primarily Open Banking-based settlement model — effectively bypassing card rails and interchange — while using SKU-level, CPG-funded Boosts (or some other compelling value prop) to drive consumer adoption of that payment method. Is there ever a reason/are there benefits to pursue that over the current approach?