The structure of B2B payments markets

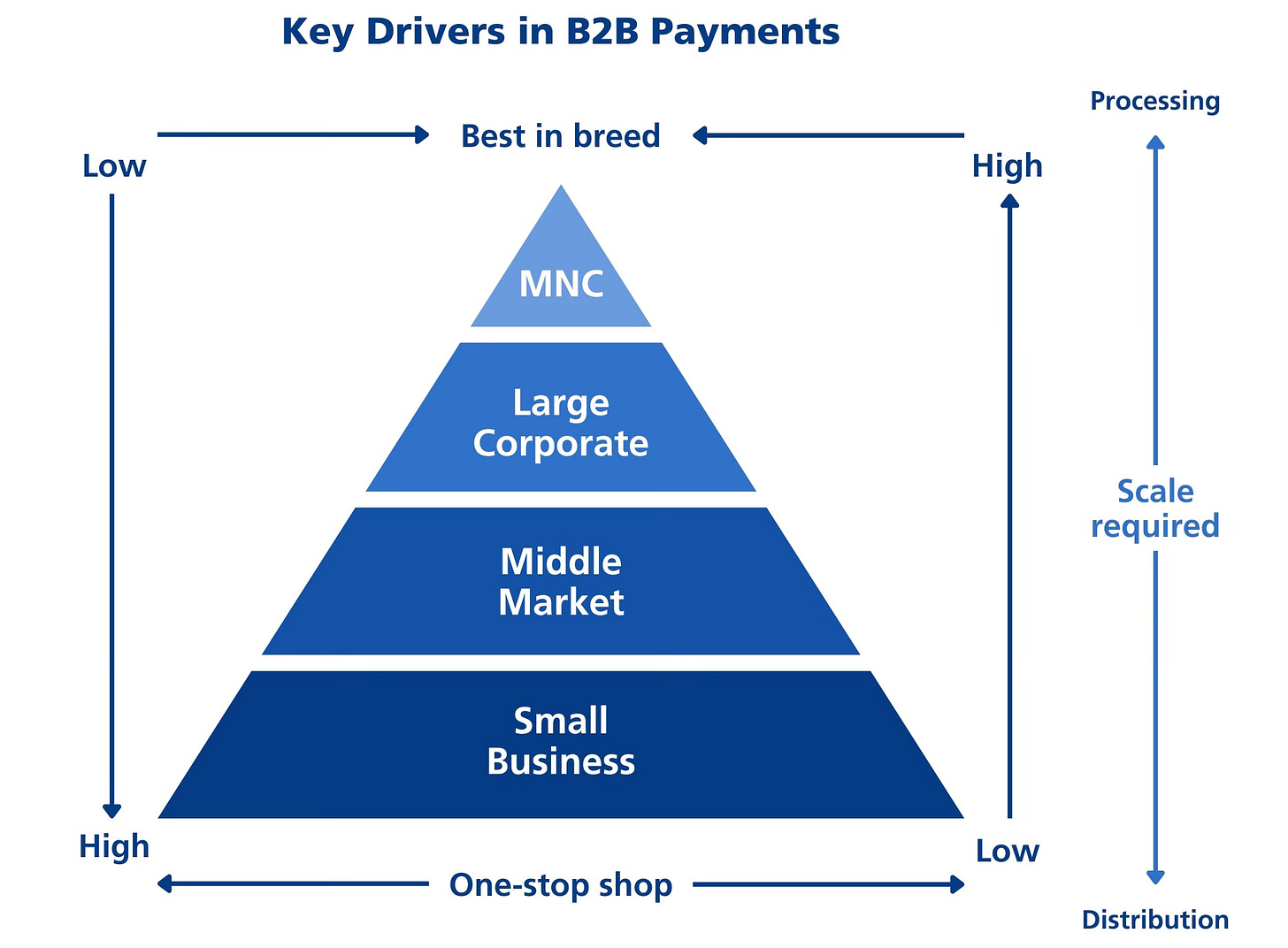

US payments processing markets (B2B) share the pyramid structure shown above. The economics and competitive landscape change systematically as you go from the tip to the base – often determining the prospects for incumbents and insurgents.

In Enterprise (MNCs & Large Corporates), volume per client is high but revenue per transaction is low. Despite low per transaction prices, margins can be very high for scale providers with low marginal costs. But where a scale provider sees high margins, a Tier 2 provider may see no margin at all.

This drives most Enterprise volume to the highest scale providers: In domestic acquiring, to the biggest four acquirers; in Treasury Services to the biggest 3 banks, and in commercial cards, to American Express and the biggest Treasury services banks (depending on product). As we will see, expanding the market beyond domestic volumes changes this calculus.

The biggest clients also don’t buy product bundles as such. They buy individual products with a best-in-class/lowest price mindset; and, the very biggest enterprises may demand customized solutions. The economic leverage for sellers comes from having enough share of wallet to support a coverage team. Here the biggest banks have an advantage since they are not only selling payments, but lending and capital markets services as well.

At the base of the pyramid, the Small Business segment has high revenue per transaction, but transactions per client are low – so the total revenue opportunity per client may not be high enough to cover distribution and servicing costs. The biggest challenge in serving Small Business is efficient distribution.

However, the Small Business segment likes product bundles, as it reduces complexity and often comes with a price concession. Many providers pursue an “ARPU” strategy to sell as many products to each client as possible. For banks, that includes deposits, cards, and acquiring. For Fintechs, it is business software, acquiring, payouts, payroll, etc. The incremental products may have higher margins than the core products, increasing both aggregate revenue per client and average margin per client.

The Middle Market segment falls between the extremes – volumes are higher than in Small Business while price per transaction is higher than in Enterprise. The segment is open to bundles that reduce integration costs. Distribution costs are lower than SB, but require a higher skilled, more expensive sales force. Banks are advantaged here as the primary lenders to middle market companies, as such lending often obligates the client to use their lenders’ Treasury Services and commercial cards. But most banks lack a competitive acquiring offering to flesh out the bundle.

Deeper dive on Enterprise

The Enterprise segment accounts for the largest share of volume but has the lowest revenue per transaction. There are few actual clients to serve in Enterprise and those clients typically buy on price – with limited prospects for cross-sell. It isn’t that Enterprise clients won’t buy additional products from a provider, it is just that all those products must be best-in-breed and low price. Enterprise clients will also integrate third-party services rather than use a bundle. In some cases, they will use more than one supplier for redundancy and future negotiating leverage. In other words, Enterprise clients don’t allow their supplier relationships to govern economic arrangements.

Only the largest, scale providers can economically serve the Enterprise segment. This dynamic leads to extreme supplier concentration. In Card issuing, it is Fiserv’s Optis and Global Payments’ TSYS that process for virtually all large, outsourced issuers. In commercial card processing the bulk of issuers use TSYS. In Treasury Services, JP Morgan, Bank of America, and Wells Fargo collectively capture over 60% of all ACH origination volume, driven by their scale in Enterprise..

Nevertheless, Fintech insurgents have taken share in Enterprise; they target narrow products or sub-segments with tailored offerings. For example, while the scale acquirers had a price moat for domestic volume, they were not truly global; but, the largest digital goods companies operate in 100+ countries and need hundreds of local payment methods. Incumbents were not present in enough geographies and they were card-centric where many clients needed Alternative Payments Methods (APMs). That left an opening for specialist fintechs to serve the global digital goods companies in gaming, gambling, media, app stores, etc.

Companies like Adyen & Worldpay built a truly global infrastructure to serve these emerging MNCs – delivering 150+ countries and 300+ APMs on an integrated platform. It helped that digital goods were among the fastest growing payments segments. This infrastructure also became useful for omnichannel global retailers and global platform companies like marketplaces. Previously, all these global clients needed different acquirers in each market and might need to integrate with APMs themselves.

Effectively, companies like Adyen found a fast growing enterprise niche (global digital goods) that eventually gave them enough scale to compete for some domestic card volume. Other Fintechs pulled off similar global moves: Payoneer in payouts, Flywire for Education payments, and, arguably, American Express in Corporate cards. Being born global creates an entry point to MNCs despite the incumbents’ domestic scale advantage.

Stripe accomplished the same outcome, but started from the opposite direction. They initially provided a payments API to eCommerce start-ups that delivered absolute simplicity – famously, “six lines of code”. But some of those start-ups grew up to become enterprise clients with global footprints, so Stripe globalized. Today, it is competitive for global merchants – and even won a chunk of Amazon. Stripe also processes for Shopify, which may account for as much as 20% of US internet spend. In other words, Stripe gained scale because its clients outgrew the market.

PIN Debit is the exception that proves the rule. The US has 5 national PIN debit networks: Interlink(Visa), Maestro(MasterCard), STAR(Fiserv), NYCE(FIS), and PULSE(Discover). Why 5 when most other processing markets get down to 2-3? The government. Prior to the Durbin Amendment, most large banks only had Visa & Interlink or MasterCard & Maestro on their debit cards. The smaller networks bundled their network offerings with debit processing targeting smaller banks. But, when the Durbin Amendment required every debit card to carry two “unaffiliated” networks it gave smaller networks placement on big bank debit cards.

In Enterprise, client M&A actually shrinks the payments TAM. When a large client buys a smaller client, the seller’s volume transfers to the buyer’s contracts at a lower price per transaction – the combined entity rises toward the top of the pyramid. This happens in bank mergers for network contracts and issuer processing and it happens in merchant M&A such as Amazon buying Whole Foods or Kroger buying Albertsons.

Generally, Enterprise markets end up with 2-3 contenders – in part, because enterprise buyers often need a backup processor for disaster recovery. At the extreme, a single processor serves most of the market, as has happened in Commercial Card processing with TSYS, or Fiserv’s Checkfree for consumer bill pay , or ACI for debit switching.

Such concentration often breeds complacency among the leading providers, with slowing innovation. The response can be client openness to insurgent solutions or the biggest clients moving in-house. Notably, in ACH the two biggest originator banks (WFC & JPM) have in-house systems while most other banks use Fiserv’s PEP+; in consumer cards, the biggest 2 issuers are in-house while most of the rest use Fiserv or TSYS, etc. In consumer bill pay, Fiserv’s Checkfree has majority share, but the biggest banks insource processing while insurgents like Paymentus emerged with better experience. In other words, concentration down to one often sows the seeds for energized competition.

Another implication of low prices at larger enterprises is that it gives those companies a cost advantage over their competition. Famously, the largest retailers pay lower card interchange, translating their retailing scale to lower cost of acceptance. The biggest retailers also get the best Cobrand deals, with rich rewards proposition driving higher consumer loyalty and higher revenue share from issuers. These big retailers can either make more margin at the same retail prices or pass the savings to consumers to build volume. Similar dynamics are at work in Treasury Services and other Enterprise payments verticals. The biggest clients translate lower payments processing costs into better overall performance.

Deeper dive on Small Business

Small businesses are largely price takers who like product bundles from fewer suppliers. The challenge for providers in SB payments are distribution cost and risk management.

SBs are hard to aggregate. Inertia keeps them with their incumbent without a really good reason to defect. Highest among those good reasons is price. Unlike larger companies, where conversion costs create a barrier to exit, many SBs can often convert manually.

To compete on price, providers often used complex price formulas to limit comparison shopping. This was most common in merchant acquiring with Qual/Non-Qual pricing. The acquirer would quote a low rate for the Qual (qualifying) transactions, which applied to standard credit cards. All non-standard cards had Non-qual (non-qualifying) rates, often one rate for each card type. Non-qualifying cards could include business cards, corporate cards, Amex cards, affluent cards and other high-interchange variations. They might also include ecommerce or other CNP transactions. Exception items had the highest rates of all, particularly key-entry transactions.

Over time, the non-qual transactions outgrew the qual transactions, so the average price of acquiring kept going up. I had a friend who had a qual rate of about 2.5% but his average acceptance cost was 4.5% – because so many of his transactions were non-qual.

Then Square shook things up. SB operators didn’t understand Qual/Non-qual pricing, but yjru knew they were paying more than they wanted to. Square radically simplified the whole scheme: they offered a flat percentage for all card types plus a fixed fee per transaction. Today that rate is 2.6% + 10¢ for most transactions. Merchants loved the simplicity.

The Square pricing model delivered predictability and transparency, although not always a lower all-in cost. The common rate covered both high-IC credit cards and lower IC signature debit. The Dubin Cap on regulated debit actually delivered a windfall to acquirers using this model.

Another innovation Square pioneered was to address the distribution challenge. Non-bank acquirers relied on armies of commissioned sales staff to call on small merchants, while banks cross-sold acquiring to small businesses opening checking accounts. Square differentiated on software and inexpensive hardware solutions and was able to get small merchants to self-onboard. Instead of an expensive, dedicated POS terminal they provided a cheap card swipe dongle that plugged into any mobile device. It’s solution was loaded with software that helped owners run their business. Square then relied on other marketing channels to drive inbound demand.

This model, of software plus payments, has become the norm in many SB verticals and can create a virtuous cycle where early adopters recommend a solution to other SBs. Toast is an example of this: They use feet-on-the street in new markets, but the quality of their software creates positive feedback loops with new merchants using self-service channels. Many verticals have seen specialists emerge and take significant share from undifferentiated competitors. This model requires vertical-specific software which can be hard for a horizontal distributor to match.

Fiserv’s Clover has created a hybrid model to address this situation by developing competitive software for several verticals but distributing through partner banks and other intermediaries. BILL does somerhinf similar in the AP/AR space.

Small Businesses can also be reached via mass marketing channels. In Credit Cards, American Express has ~50% share of the SB card market despite having no direct channel to small business owners. And Capital One Spark is among the top 3 issuers despite a rather limited branch footprint. Chase INK rounds out the top 3 using both national marketing and branch cross sell. While #4, Bank of America leans on branch cross-sell. Competitors either need a captive distribution channel (branches) and/or a national brand – both are expensive and scale driven.

These mass market techniques work for standardized products that don’t serve the needs of every SB. So insurgents (e.g., Ramp, Brex, Divvy) created a new wave of “Expense Management” card products that serve tailored niches – like startups. They initially collateralized card spending with the startup capital sitting in the startup’s bank account. They have since moved to more conventional credit underwriting to broaden their audience, but they started by targeting a small niche that the big issuers didn’t serve well. And all this was supplemented with expense management software that routed card spending to the right costs centers and GL lines without extra effort – simplifying expense reporting. This model is now moving up-market.

While small businesses don’t use Treasury Services in the same way large businesses do, they still need cash management, and fintechs have moved to serve that need. While some of these companies monetize via fees, others have used virtual cards to earn revenue at no cost to their clients (suppliers pay the interchange). So the SB gets better cash management while their suppliers bear the cost.

Deeper Dive on Middle Market

The biggest challenge in discussing the middle market segment is defining it. At the low end it bleeds into small business and at the top end it bleeds into Large Corporate. Many large banks subdivide by vertical or by segment (“lower middle market” versus “upper middle market”). Roughly speaking, the low end can be as low as $10M in annual revenue and the high end, $1B in annual revenue, but every entity that serves middle market has its own definition.

Banks are typically central to middle market payments. Middle Market companies rely on bank lending rather than capital markets for their funding – and that lending comes with some obligation to use the lender’s Treasury Services and Commercial Cards. The commercial bankers also provide entree to distribute their bank’s payment services at low CAC relative to Fintechs. In general though, Fintechs have made fewer inroads into MM payments than they have in the Small Business segment.

This segment pays less per transaction than small businesses, but more than Enterprise. For acquiring, the middle market marks the transition from Merchant Discount Rate (MDR) pricing to IC+ pricing. MDRs are a percentage of face value, (i.e., acquirer fees are in basis points), while IC+ passes through interchange and network fees and the acquirer takes a fee in cents per transaction. For commercial cards, the rebates back to MM companies are lower than those for Enterprise because volumes are lower. Treasury Services are usually priced in cents per transaction with per transaction fees falling as volumes grow.

Middle Market companies are more open to bundles if they are pre-integrated. They often lack the tech resources to integrate themselves. But they are not good targets for some of fintech lending services, where banks have a big cost of funds advantage.

Although bank lending is verticalized , banks typically don’t verticalize their payments offerings, leaving an opening for Fintechs. Flywire is an example here; serving the cross-border payments needs of three middle market verticals: Universities, Hospitals, and Travel companies. For universities, Flywire helps collect expat student tuition payments by allowing the student to pay in local currency using local payment methods from their home country; It then moves the money to the University in their native currency with direct integration into their ERP. Basically the same model serves hospitals for medical tourism. For travel, Flywire serves luxury experiences like Safaris. All three are high ticket venues where credit cards are expensive but ordinary money transfer is inconvenient.

For the biggest verticals, the biggest banks do tailor their payments products. Both JPM (InstaMed) and BAC (AxiaMed) offer payments portals to help Hospitals collect consumer responsibility payments. Most verticals get standard offerings.

As a result, fintech models have moved into lower middle market to automate accounts payable and receivable. These Fintechs focus on Verticals where AP and/or AR are a particular paint point. Their Software helps the company automate processes even if the payments are still executed by a bank. Many of these fintechs monetize via virtual cards which rebate some of the interchange back to the payor.

Key insights on B2B payments

The requirements to win are very different in the three macro segments

In Small Business, distribution and software depth are differentiating while price needs to be transparent. Software may need a vertical dimension. Small businesses like bundles and will often opt for the value added services of an incumbent to avoid integration costs. The market can support more than a few competitors focusing on different segments and verticals

In Enterprise, processing scale is necessary to offer low per transaction prices, but scale providers can still make high margins. This concentrates the market among a few providers, Enterprises don’t buy bundles unless each component is least cost and high functionality

Middle market is a mixture of the the two other segments, but banks have a distribution advantage as they are the primary lenders to these companies.

The strengths and weaknesses of banks and fintechs are complementary, suggesting there is room for partnerships where banks provide distribution and fintechs provide software. Fiserv Clover is an example of where this is working