Key insights in this post

Neobanks grew rapidly during the Pandemic, leveraging the tailwind from stimulus payments for low-balance consumers. They claimed a few key advantages:

Free to the consumer

Digital only with a superior UI and lower servicing costs

Innovations like 2-day advance payroll and discounts

Exempt debit interchange while big banks earned the regulated rate

They planned to diversify into other services as customers grew more affluent

After four years in market, that model has not worked out well:

No Neobank makes material profits and unit economics are not inspiring

No Neobank has moved upmarket and would undermine their revenue model if they did

No Neobank has grown material balances and they have no market advantage with higher balance consumers

Their innovations were copied by incumbents, especially 2-day advance payroll

While most Neobanks don’t disclose their financials, Varo bank does and those financials demonstrate why the model is so challenging

Neobanks are unlikely to break out of their low-balance niche as they have no meaningful advantages in other products or segments

Introduction

Neobanks emerged during the Pandemic. Unbanked consumers needed direct deposit to get stimulus payments, but opening a bank account in person was challenging during COVID. Further, low-balance bank accounts from incumbents often had minimum balance fees or restricted functionality.

Neobanks were digital-only and free. They offered attractive add-ons like 2-day advance payroll, discounts, and, in some cases, advances. They claimed a superior digital experience. Millions of consumers took their accounts.

Neobanks earned more on a debit-centric, low-balance account than incumbents because they were Durbin-exempt. They claimed digital-only made them cost-efficient enough to earn a margin on low-balance revenues – mostly Exempt debit interchange.

In 2021, Chime was estimated to have 12M accounts, and several other Neobanks claimed multiple millions. Doomsayers predicted the end of incumbent banks. Of course, that never happened, but it is important to understand why.

I have been a long-time skeptic of the Neobank model, since 2020 in fact. I track the financials of Neobanks that publish them. The best case study is Varo Bank – the only Neobank with an actual bank charter.

Varo financial performance

As a chartered bank, Varo publishes quarterly call reports. The Q3 2024 report just came out so we have four years of history to track growth. Note that I am using Varo only because they made the brave strategic decision to get a charter. Most other Neobanks use a BIN-Sponsor and their financials are not public.

While Varo was founded in 2020, their 2020 call reports are inconsequential. I focus instead on Q3 data for 2021-2024. Note that these are for the first 9 months of each year. I wasn’t patient enough to wait for the year-end reports!

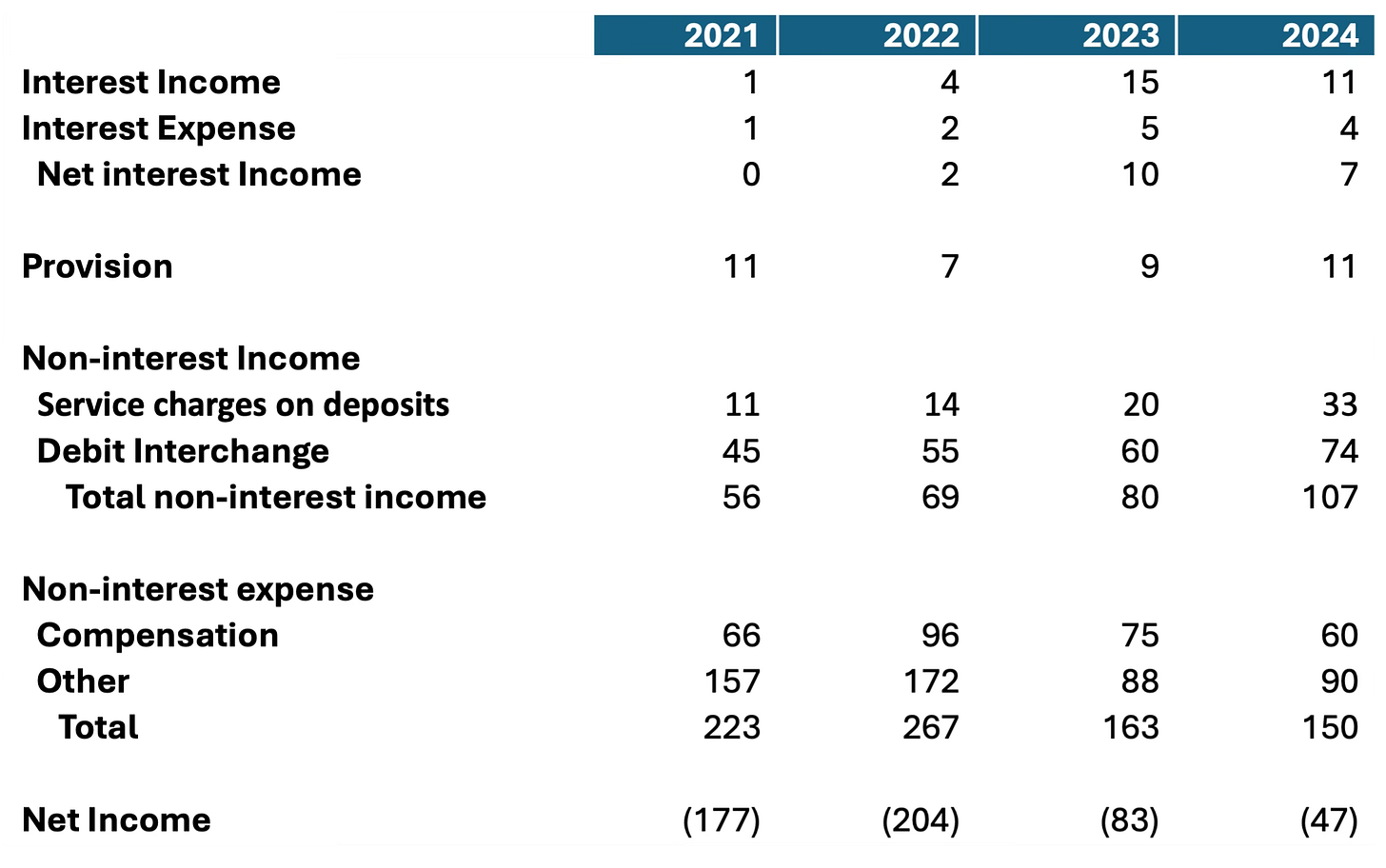

Varo income statement, Q3 Call Reports (9 months) ($M)

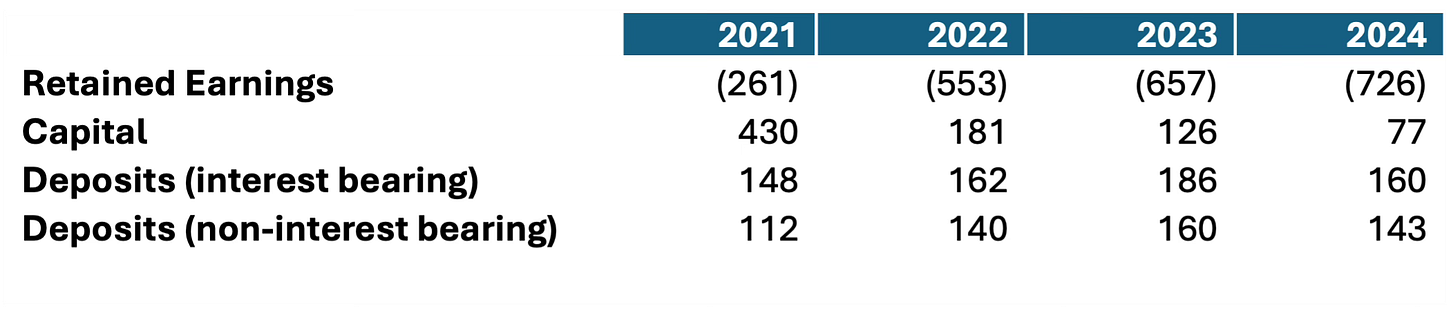

In 2020, Varo was founded with $123M in capital. In 2021, investors publicly contributed $518M more during the early pandemic enthusiasm for Neobanks; Investors added $80M more in subsequent years. They have cumulatively lost $726M over this period.

Selected balance sheet items, Varo Q3 call reports

($M)

Varo is financially unsuccessful, but their business performance isn’t great either. Deposits are effectively flat over the last three years.

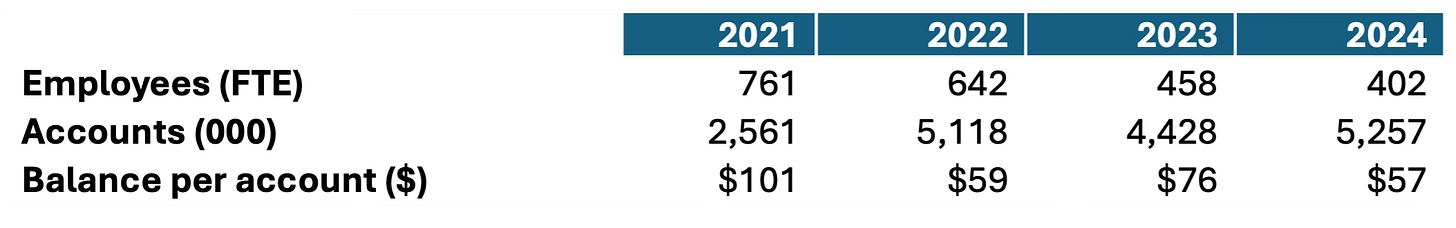

Selected operating metrics, Varo Q3 call reports

Nominal deposits per account have dropped below $100 but I do not take this at face value. Varo likely has millions of dormant accounts and a smaller number of debit-active accounts with more meaningful balances. I calculate that about 90% are either savings accounts or dormant transaction accounts; that adjustment yields an average balance per debit-active, non-interest bearing account of $275-375 — still very low.

More than half of deposits are interest-bearing. Varo pays 5% APY on the first $5K of balances and 3% thereafter. Many accounts may be there just to get that 5%. Their annualized interest expense divided by their interest-bearing balances is close to 3.5%. High-yield accounts tend to shift to the highest offer, leaving behind lots of dormant accounts

Varo’s debit interchange revenue could only support around 500K debit-active accounts. If we assume a debit-active account does 35 transactions per month at an average of $0.45 exempt interchange (IC) per transaction, we can estimate debit actives. In Q3 2024, $74M in IC / $0.45 per tx / 9 months of activity / 35 monthly txs per account = 521K active accounts. That is roughly 10% of their reported accounts. The 2024 average non-interest bearing balance for those active accounts would be $274

Varo are not a big lender with only $71M in loans, but their net interest income is below their provision, so they lend to poor credit risks. These are mostly low-value cash advances and secured credit cards. For deposits, they added ~750K new accounts for 2024, but balances actually declined. One bright spot is fee revenue, which was up – so engagement is on a positive trajectory.

This overall economic picture is not pretty. They accumulated half a million active accounts, but lost money on that base. This undermines most of the claims for Neobank superiority; those arguments include:

Exempt Debit offsets the need for other fees

Their digital UI makes them a preferred choice

Branchless banking lowers costs

They can eventually move upmarket and diversify

Neobank innovations create a moat

I challenge each of these claims:

1. Exempt debit economics do not lead to positive account economics

The vast bulk of Varo revenue is fee-based: Exempt Debit Interchange (~70%) and other fees (~30%). The other fees are mostly out-of-network ATM fees. While Vary provides free ATMs via Allpoint, many customers still use out-of-network machines. The total monthly revenue per estimated debit active is $23. In contrast, monthly NIE per debit active is $32.

Part of the reason for this is that not all Debit interchange earns published Exempt rates. Some networks compete for debit routing rights by discounting Exempt interchange, particularly at the biggest merchants. Unfortunately for Neobanks, debit-centric consumers concentrate their spend in Everyday spend categories where the biggest merchants have high share – so a high percentage of debit transactions generate discounted exempt interchange. The Durbin moat is leaky.

2. The UI is only better for a single-product, low-balance customer

I once did a side-by-side comparison between a major bank’s digital UI and a major Neobank’s. I found that they both provided roughly the same functionality and experience with the notable exception of 2-day advance payroll – which is an economic feature not a UI feature. The bank had free, entry-level checking accounts, Cardlytics-driven offers, and a well-regarded UI.

But, the bank’s digital channels were optimized for multi-product households while the Neobank’s focused squarely on the low-balance transaction account. That made the Neobank UI easier to navigate if all you had was a transaction account — but this would not meet the needs of a multi-product customer.

Since most incumbents can’t make a meaningful profit on low-balance, debit-centric households, they have no incentive to invest in a tailored solution for that segment. Neobanks have the market to themselves.

3. Branchless banking is not less expensive than branch banking on a marginal cost basis

The constant refrain that digital banks have lower costs than branch banks is not accurate – even though people have been saying it for 30+ years. Yes, Neobanks don’t have branch overheads, but they also don’t have the branch’s marketing value (“the billboard effect”). Most consumers still open their checking account at a local branch and then service it digitally.

Instead of walk-in traffic, Neobanks drive origination via advertising – a lot. In 2023, Varo’s advertising expense was $21M – almost 25% of income. That was down from $85M at the end of 2022 (higher than total revenue). In addition, Varo pays high APYs on savings to attract households that can be cross-sold a transaction account; that interest expense can be thought of as a marketing expense. They pay 5% on savings whereas JPM pays 0.01%.

Free ATM access has a cost, as Allpoint charges transaction fees. Those costs are not disclosed, but the all-in cost may be as high or higher than the cost to own physical ATMs in branches. The Allpoint fees grow directly with volume whereas physical ATMs are mostly fixed cost – scale improves their economics. Most bank ATMs also earn some interchange and surcharge revenue from off-us transactions, which Neobanks can’t do.

Finally, Varo has 402 employees, at least some of whom must sit in call centers, just like incumbent banks. Not everything can be done through the mobile app or web site.

Volume growth will not solve the cost problem. An NIE breakdown is only provided in the year-end call reports, but last year, most expenses had a limited fixed cost component. The biggest category is data processing which is likely sourced from a core processor on a per account basis. In other words, volume increases alone will take a long time to turn account level economics around because there is no scale effect from leveraging fixed costs.

The other side of the comparison is unfair to incumbents. They have plenty of customers who never visit the branch after opening their account. I visited a branch once in the last 3 years, beyond ATM transactions; so, the marginal cost to service my account is trivial. Allocating branch costs to digital-only customers is the fallacy here. For a digital-only customer, marginal costs are equivalent between an incumbent and a Neobank. The incumbent may even be more cost efficient due to scale.

4. Neobanks cannot go upmarket without undermining their model

Over of the long-term, neobanks expected to ride the lifetime income curve to glory. As their customers aged, they would reach prime earning years where transaction balances rise. Further, as the Neobanks learned about their customers, they could start lending to them, generating an additional revenue stream. Some customers might even need wealth services eventually.

None of this happened — and it would cripple Neobank economics if it did. Let’s start with size. A Neobank relies on exempt debit interchange for 70% of revenue. If they ever got big enough to exceed the Durbin $10B asset threshold their debit income drops by up to half. Chime solved for this by splitting its volumes across two exempt BIN-sponsors: Bancorp Bank & Stride Bank. Will regulators allow that solution indefinitely? After all, Durbin has anti-circumvention language.

Further, as customers get more affluent, they will find less to like about a Neobank:

Consumers get free checking at most incumbent banks once balances exceed $500 with direct deposit or $1,500 without. At those balance levels, the Neo account has no economic advantage. In fact, the Neo account may be more expensive because an incumbent has a proximate ATM network with less need to go out-of-network

All incumbents offer Zelle, while Neobanks can’t join — a disadvantage. As an actual bank, Varo has Zelle — but this raises costs without offsetting revenue

Customers will migrate spend from debit to credit, but Neobanks have no Durbin-equivalent moat in Credit. Once the consumer moves to credit, 70% of revenue walks out the door (Debit IC). Credit is dominated by giant issuers with scale economics and rich rewards propositions; Neobanks would have a tough time keeping customers on a sub-standard card

Consumers may need multi-product support (e.g., Card, Mortgage, Wealth, etc.). Not only do Neos not offer most of these products, but their simple UI would get more complex if they did. UI simplicity is their advantage with the low-balance customer. In contrast, big banks have finely tuned multi-product apps & websites

5. Neobank innovations are not proprietary

The most important Neobank innovation has been two-day advance payroll. Most Neos advertise this extensively, as it is important to the customer base they serve. However, not only did they copy this from each other, but the big banks copied it as well.

Capital One & Fifth Third did this first, but JPM, Wells, Huntington, Regions and others also do it now. It will become table stakes going forward. A key Neobank advantage beyond “free” is becoming a commodity.

Are other Neobanks doing better?

The two biggest Neobanks are Chime and Cash App. Cash App is not a pure Neobank as its genesis is in P2P payments, but it now offers debit cards, direct deposit and a variety of other financial services. Chime has diversified into secured credit cards. Chime recently claimed 7M active users, while Cash App claims 57M P2P users, 24M of whom have a debit card, and ~2M+ of whom have direct deposit.

Can these two make a go of the Neobank model given their scale? The jury is out, but here is the evidence:

Cash App

Block helpfully provides financial and operational data on Cash App. The last time they reported Direct Deposit actives (March, 2023), they had 2M accounts. That would make them roughly 4x bigger than what I estimate for Varo. On the other hand, they claim 24M Cash App Card actives. Many customers seem to use the card to spend down their P2P balances, not as a primary transaction account.

Cash App uses Sutton Bank as their BIN Sponsor, so balances must reside on Sutton to get FDIC Insurance. Sutton reports ~$1B in deposits in their call report that could be attributable to BIN Sponsoring. That means average balance per direct deposit account is ~$500 – higher than Varo, but still low-balance.

Cash App has its P2P service as a distribution channel, so it needs less marketing spend to source customers. They get their debit processing from Marqeta on a sweetheart deal – so Marqeta shareholders subsidize Cash App economics. Overall, the Cash App segment is profitable, but the contribution from their Neobank-like services (accounts with direct deposit) is a small fraction of that profit.

Sutton Bank’s in-scope deposits were down by almost one-third from last year. Far more than the increase in balances at Square’s captive bank. That suggests the use of Cash App as a transaction account is on the decline. It is also suspicious that Block didn’t report Direct Deposit actives in March after doing so the prior two years.

Chime

Chime has far less data in the public domain, so any measure of size and growth is speculative. Their CEO gave a Forbes interview in May that released some tidbits: He claimed they have 7M active accounts, were profitable in Q1, but lost $200M in 2023.

He also said they had $8B in debit spend per month and 2023 revenue of $1.3B. If we do the Varo math on these numbers we can reconcile the $8B monthly spend with the $1.3B annual revenue: $8B per month * 12 months / $45 average debit transaction * $0.45 interchange per debit transaction = $960M. Debit IC is around 70% of revenue at Varo. If the $960M is 70% of revenue, then total Chime revenue would indeed be ~$1.3B. These stats also estimate ~5M debit-active accounts – pretty close to the claimed 7M if we assume some dormant and savings-only accounts.

The Neobank economic formula seems similar between Chime & Varo. Dividing Chime revenue by the estimated number of active customers yields approximately $21 in monthly revenue per account. Varo earned $23.

In terms of balances, it is even harder to compare. Chime uses both Bancorp Bank and Stride Bank as its BIN sponsors and we don’t know what the split is. Further, both these sponsors have other customers, so not all balances are Chime balances.

Chime’s unit economics seem similar to Varo’s. Chime operates at higher scale which may be how they eked out a Q1 profit, despite losing $200M in 2023 (the equivalent Varo loss was $105M on 0.5M debit-active accounts). For 2023, Chime likely lost $29-40 per active account annually.

Money Lion & Dave

I won’t spend much time on these, because both have pivoted from the pure Neobank model. Both have public financials, which show a similar story:

Money Lion pivoted to a marketplace strategy, distributing other providers’ products. They were profitable YTD in 2024, but had a Q3 loss

Dave started as a lending business. It uses its ExtraCash advance product as an anchor to upsell the Dave Card transaction account. They claim 11M+ members, but only 2.3M transact on the debit card. Customers don’t seem to transact very often. My math shows 15 annual purchases per card or ~4% of normal debit usage

In other words, neither of these companies follows the Neobank blueprint and neither is particularly profitable on their Neobank operations.

USAA

I am cheating here to make a point. USAA serves many low-balance customers, especially enlisted service members. It is mostly digital with only 4 branches. According to its call report USAA has 13M accounts and $81B in deposits. It is profitable.

The main differences between USAA and Neobanks is marketing and product mix: As an Affinity, USAA gets a CAC lift. It does spend ~$300M on advertising across a product portfolio including Credit Cards, Insurance, & Investments. USAA gets, the lower, regulated debit interchange rate, yet is still profitable. Navy Federal CU is a similar story, but even bigger!

USAA is over 100 years old. The message here is that Neobanks aren’t even that Neo!

Conclusion

I wrote a document like this in Q1 2020, but had no data to back up my argument. It was peak hype for Neobanks, so the thesis was a hard sell. We now have proof that no pure-play Neobank makes material profits after 4 years, and all of them are having trouble diversifying or going upmarket. While they have a moat from Durbin interchange – keeping incumbents out of the low-balance segment – that moat also keeps the Neos trapped in a market with marginal economics.

I doubt incumbents give Neobanks a second thought now, but for any who do, stop!

Thank you Caribou. I was entirely focused on the US, so $NU would not be in-scope, but I agree completely that this lending-first model works better than the transaction account-first model of US Neobanks. For better or worse, I don't think of Lending Club or SoFi as Neobanks (which was Sal's point). If I have a defense it would be that this is a payments blog and the lending-first US models are not really payments-relevant. The transaction-first Neos rely on a Durbin moat and are payments relevant. Of course, Affirm, Klarna, AfterPay et al. are payments-led lenders, but they don't yet offer deposit accounts that I am aware of, so also not Neos. But I likely should have at least commented on SoFi & Lending Club if their deposits are meaningful. I will check! Thanks to everyone for the comments! I was hoping to generate conversations with these Post but this is the first one that really had any.

Thank you Alan! I am a bit blind on the European situation, which is why I stick to North America, but this makes sense to me. The US is less fertile territory for a multi-currency wallet of course, so this particular tactic would be less effective here