Key insights in this post

JPM announced that it will charge fees to access its data APIs; the Fintech lobbying group, the American Fintech Council (AFC) forcefully opposes this

This was triggered by the likely end of the CFPB’s Rule 1033 which was challenged in court and withdrawn by the CFPB – which returns us the Contract Regime that has been operating for the last 5+ years

JPM’s announcement and the AFC’s response agree on some topics that are also consistent with what Rule 1033 would have mandated

Consumers can permission their data to any third-party that keeps it safe

Generally, all consumer data is available for aggregation

JPM & AFC disagree on more topics with each deviating from Rule 1033 in some areas

JPM wants to charge Aggregators for access while the Aggregators want the data for free (Rule 1033 was on the AFC’s side)

JPM today limits access times and frequency to constrain capacity demands while the AFC wants no frequency limitations (Rule 1033 required “reasonable” constraints — with “reasonable” defined by consensus)

JPM wants to limit data use to the specific purposes authorized by the consumer while Fintechs want to use that data for other purposes (Rule 1033 is on JPM’s side)

JPM wants the AFC’s members to assume liability for data breaches and other bad outcomes while the AFC is silent on this issue

Rule 1033 left this issue open to a consensus process among all parties

The current bank contracts shift liability to the Fintechs & Aggregators

Importantly, the data is not free today to the end Fintechs, but only to the Aggregators. The Aggregators themselves charge fees to end Fintechs

I identify key issues that inform whether the fees are fair or unfair

How steep are the fees?

The fees are rumored to be modest except for “payments related fees”

Payments-related fees likely refer to the one-time capture of the DDA account number rather than ongoing payment transactions

The Fintechs have alternatives to getting account numbers if they find the API fee too high

Will the Aggregators pass through 100% of the fees?

The rumors suggest big Aggregators will benefit from tiered volume pricing that should allow them to underprice smaller aggregators

Aggregators won’t have to pay fees for screen-scraped data from smaller banks which represent 30% of consumer accounts

Aggregators may absorb some of the cost to capture more volume

If 100% is passed through, how material are the fees to end-Fintech financials?

We don’t yet know the aggregate size of the fees, but they will clearly impact origination data and transaction data differently

For origination related data, the fees are likely to represent a modest increase in CAC — well under 5% in most cases

For transaction data, the impact could be substantial

End-Fintechs have ways to minimize the impact including taking less data and taking different data

Banks have ways of limiting the impact include discounts for PFM and GL type services and two-tier pricing that discounts for data accessed in off-hours

What is the impact of data use limitations?

The JPM position on data usage is consistent with both the status quo and Rule 1033 while the AFC position is silent on this topic

Banks are concerned about compliance and liability if the data is repurposed beyond the disclosed use case

Fintechs want the freedom to use data for use cases which may not have been clearly disclosed in their initial permissioning

JPM has the better of the argument in my opinion

Conclusions: After all the puts and takes, this comes down to the price schedule:

End-Fintechs already pay for this data, they just pay the Aggregators instead of the banks. Those prices will likely rise given JPM fees, but should be affordable given the value delivered

If Banks charge fees that are too high Fintechs have work-arounds available:

Take less data to reduce the aggregate cost

Get Aggregators to absorb some of the cost to keep the volume

Get similar data in other ways at the cost of some friction

If the fees are affordable and become universal, they could actually improve the system for all parties

Smaller banks may introduce APIs through their processors, eliminating Screen Scraping for the 30% of consumers that use those banks. 1033 would not have required this

Larger banks may open up their APIs to new time windows and data services since they are remunerated for their efforts

Banks and Fintechs may partner more to internalize these costs with banks provide distribution and Fintechs provide solutions and innovation

All things considered, Consumers get a better deal: Ready access to innovative services with lower risk to their privacy and security at no direct cost to themselves

Introduction

Judging by the hysteria it triggered, JPM’s introduction of fees to access its customers’ data was the apocalypse for Fintechs. The reality is more mundane.

With JPM’s announcement, some costs shift around but the key features of the system don’t: Consumers can still move data to Fintechs via Data Aggregators and Fintechs will still pay for that data. What has changed is that JPM will start charging Aggregators a fee for accessing the JPM infrastructure. The Aggregators can either absorb those fees or pass them through to the Fintechs. That either means lower Aggregator margins or higher Fintech costs.

This is unlikely to be a major revenue source for JPM, but will incent efficient behavior by aggregators and potentially fund capacity to give the end Fintechs more flexibility – at a price.

In this post, I review how all this works pre-contracts, under the contract regime, what Rule 1033 would have imposed, and the post-JPM environment. I discuss the CFPB’s rule 1033 in this post. It is the withdrawal of that rule that brings us to where we are.

I have conflicts on this topic. I work part time for a large bank and I was peripherally involved in JPM’s pioneering contracts with the Data Aggregators in the mid-teens. Reader beware!

What did the parties actually say?

I chose the two announcements that officially summarize the respective positions.

JPM 2024 Shareholder letter (bolding in original):

“Third parties want full access to banks’ customer data so they can exploit it for their own purposes and profits. Contrary to what you may read, we have no problem with data sharing but if it is done properly: It must be authorized by the customer – the customer should know exactly what data is shared and when and how it is used; third parties should pay for accessing the banking system and payment rails; third parties should be restricted from using customers’ data for purposes beyond what the customer authorized, and they should be liable for the risks they create when accessing and using that data. When banks utilize third party data, they will be, and in most cases already are, subject to the same obligations”

American Fintech Council (AFC)

“Consumers have a right to their own Financial Data, full stop. Any effort to restrict or monetize access to consumer-permissioned financial information is a direct threat to responsible innovation, healthy competition, and the progress we’ve made towards a more inclusive financial system.

At a time when consumers are demanding more flexibility, transparency, and control over their financial lives, placing a tollbooth on data access will harm the very families a safe financial system is meant to serve. This is a shameless attempt to further entrench the position of incumbents. Open banking only works when the largest institutions embrace, not obstruct, the transparency and interoperability that drive responsible innovation. Financial institutions should be empowering consumers – not creating new barriers to access.”

Where are the friction points?

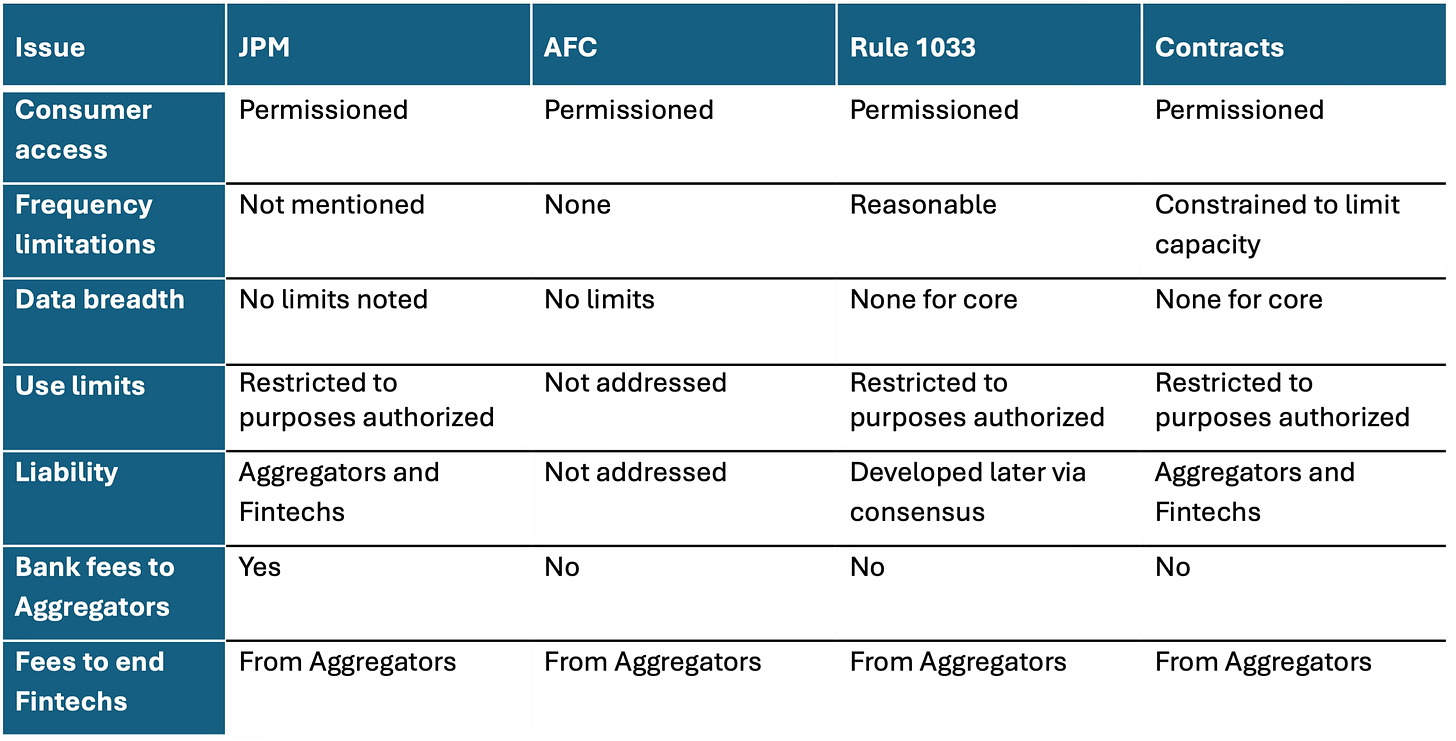

These two statements have overlap on some issue in addition to key differences. They also vary in some ways from what Rule 1033 would have mandated and what the current contract regime requires:

If I have captured this correctly, there are areas of agreement:

Consumers can permission their data to any third-party that keeps it safe

Generally, all consumer data is available for aggregation

The areas of difference are:

JPM wants to charge Aggregators for access while the Aggregators want the data for free (Rule 1033 is on the AFC’s side)

JPM today limits access times to constrain third-parties capacity demand while the AFC wants no frequency limitations (Rule 1033 required such constraints to be “reasonable”, with the definition of reasonable to be provided later).

JPM wants to limit data use to the specific purposes authorized while Fintechs want the ability to use that data for other purposes (Rule 1033 is on JPM’s side)

JPM wants the AFC’s members to assume liability for data breaches and other bad outcomes while the AFC is silent on this issue.

Rule 1033 left this issue open to a consensus process among all parties

The bank contracts shift liability to the Fintechs & Aggregators

Note that the data is not free today to the end Fintechs, but only to the Aggregators. The Aggregators themselves charge fees to those end Fintechs. The questions then become:

How steep are the fees?

Will the Aggregators pass through 100% of the fees?

If 100% is passed through, how material are the fees to end-Fintech financials?

What is the impact of data use limitations?

I will address each of these below.

How steep are the fees?

JPM supposedly sent fee schedules to the aggregators. Credible rumors suggest they are modest, vary by use case, and are tiered such that the biggest aggregators get the lowest prices. This is the crux of the issue.

One wrinkle is speculation that the fees are highest for “Payments related” data, but it isn’t clear what that means. I can think of three alternatives:

Transactions -- The contracts in place today, and Rule 1033, banned third-parties from pushing out payments as if they are the customer themselves. This is allowed in Europe under “PISP” rules but, is not allowed here. However, a third-party can have their bank submit an ACH Debit to the customer’s bank account. JPM would only see that as the Receiver of that Debit – and ACH debits are not charged to consumers today. To me, this can’t be the new fee

Balance data – Fintechs often check balances before they originate an ACH Debit. That gives ACH the equivalent of an “Auth” in the credit card system. The balance check ensures there is enough money at that moment to avoid an NSF. I doubt this is what JPM is premium pricing because avoiding NSF’s is a major positive. The cost to deal with NSFs, including unhappy customers, make it something that banks want to avoid

Account data – A major use of aggregation is to take the DDA Account Number so that it can be used for ACH debits or credits by the Fintech. This is a one-time activity unless the account number changes. This is likely what JPM is charging a premium for

Therefore, the rumored high charges for payments companies likely reflect a premium fee to get the Account Number. Of course, the Fintech can always have the customer type that number in or take a picture of a check to capture it, but those methods have friction. With the fees, bank might even introduce “push-provisioning”, similar to how cards are provisioned to Apple Pay. But the key point is that this is a one time fee for a very high value data element — and Fintechs have ways to avoid it.

Will Aggregators pass 100% through to Fintechs?

This part of the back-and-forth is maddening to me. The Aggregators already charge the end Fintechs for bank data that they get for free. If it is so outrageous that Fintechs have to pay fees to get bank data, why is it OK that Aggregators charge fees for that data. If it is so unconscionable, why hasn’t Silicon Valley created a utility to get that data for the end Fintechs for free or at cost? It would make all Fintechs more profitable. We know why they didn’t do that. It’s because Aggregators get high valuations from high growth & margins – because their COGS are free.

Assuming the JPM fees are indeed modest, what the AFC is really complaining about is that Aggregators suddenly have COGS; however, the Aggregators don’t have to pass all that cost through to the end Fintechs, they could just absorb it in their pricing. Or they could pass only some of it through.

The JPM fee structure also benefits the biggest Aggregators because the fees are “tiered”. Basically, the first tier of volume has a higher price, the second tier drops that price a bit, and so on and so on. The biggest Aggregator has more volume at the higher tiers where marginal fees are lowest. That gives them an inherent cost advantage over smaller Aggregators. In other words, if price matters, volume will concentrate into the biggest Aggregators – goosing their growth, their share and their valuations.

Further, at least a third of consumers bank with a small institution that doesn’t have a data API. These banks would have been exempted from Rule 1033. Aggregators use screen scraping to grab their data so there is no opportunity to charge fees. Nothing changes.

However, if Fiserv and FIS started offering an API service to these small banks in return for a share of the fees that Fiserv/FIS negotiate, it will accelerate the adoption of APIs – which is much better for the end Fintechs, if not the Aggregators. Note that Fiserv is itself an Aggregator through its AllData unit — so it may be on both sides of this issue.

Finally, banks may be willing to moderate flow controls for higher fees – which the biggest Aggregators could afford. That would allow new products to end-Fintechs. If a Fintech really needs a balance check multiple times during the day, today that might not be possible under the contracts. But if the banks get paid extra for peak-hour capacity they might open up the gates. Everyone in the value chain is better off.

How material are the fees to end-Fintech financials?

This depends on what JPM is charging for each transaction type. The impact will be different on Fintech’s with different business models. To grossly simplify, let’s consider two broad categories of data: Origination Data & Transaction Data

Origination data

Most financial entities of any kind already pay for originations data. In lending, they buy Credit Bureau data and FICO scores. In deposits, they pay Chex Systems, EWS, Lexis Nexis and other data sources to both check the consumer’s history and to validate identity. For other products they may buy home price valuations, stock portfolio pricing data, compliance data, etc.

Banks have the best identity data because of their KYC obligations. They spend a small fortune to make sure KYC is accurate. Some Fintechs verify identity by having their customers sign in to their bank accounts via an Aggregator and if successful, they assume the customer is who they say they are. And they likely are.

So whatever JPM charges just adds on to a longer list of data the Fintechs already pay for. But how material are JPM fees relative to the overall CAC? To use one example, when Chime went public I recall they claimed a CAC of $200 per account. Most of that was advertising cost. For every $2 JPM charges for the account validation (known as ID&V) it would raise CAC by 1%.

The Fintech can likely reduce other data sources if it gets this data, so the net cost may not be as high. In either case, this is not the difference between success or failure for an otherwise healthy Fintech. If the Aggregators absorb some of the cost it could be less.

I assume here that the JPM fee includes both the account verification and the account number. In Chime’s case, they can use that account number to fund the initial account balance rather than waiting for a check or some other form of deposit. That is high value data.

Transaction data

Here the data has more volume, but each transaction has limited value. It is only by building up a pattern that the utility emerges. One use case is budgeting (PFM); Aggregation began in the early 2000s to support PFMs via the OFX standard. Small businesses uses similar methods to download data into their GLs.

Fintechs have developed other uses for transaction data, such as marketing offers - this was how Mint originally monetized its PFM. Other Fintechs use the transaction data to underwrite loans.

Price matters a great deal here. The average debit-centric consumer does ~40 purchases per month — at 5¢ per transaction it would cost $2 per month just to assemble card data for such use cases. This is indeed unaffordable for ongoing services like PFM.

It may be affordable for underwriting. First of all, Fintechs could collect daily or monthly balances instead of transactions and get the bulk of the value at a fraction of the cost. Second, if the loan is of meaningful size and the data improves decision making, it likely pays for itself with reduced credit risk. Finally, the Fintech can avoid it all by having the consumer send in a PDF of their bank statement(s). AI can then convert the text into data. These are available from all banks via their digital channels. While they have more friction for the consumer, they avoid all the fees. If you are recoiling in horror at introducing friction, you are basically making the case that the JPM API has value.

Another alternative is that banks create bundles for solutions like PFM or Small Business GL (e.g. Quickbooks, Xero as discussed in this post).

PFM never lived up to its promise. Quicken claims 20M users over 4 decades, but noticeably does not disclose the current user base. Mint was a phenomenon in its day, but Intuit recently shut it down. Mint’s last reported user base was 3.6M and falling fast. While this application legitimately needs lots of data, it likely doesn’t impact lots of customers.

Small Business GL is the toughest case. Typically a small business wants to download all its transaction activity into its G/L to post and reconcile. The GLs themselves can’t absorb that kind of cost into their P&Ls and the SBs will hate incremental fees.

I can think of solutions to this problem although there are likely more:

Banks can offer bundles that include reasonable data access frequency as part of DDA monthly fees. This caps the capacity demand while reducing the total cost

Banks can emulate the Fintech model of two-tier pricing. For example, PayPal, Venmo & Cash App offer ACH transfers for free, but charge hefty feea for real-time transfers. Uber does this with intraday driver pay. It is a common way for Fintechs to monetize. Banks could charge low or no fees for batch downloads that operate overnight (when capacity is underutilized), but charge the normal fees for peak hour and real time access. Neither PFM nor GL generally require real-time

Fintechs could partner with banks to distribute their PFM or GL solutions. This is already common in some Fintech use cases — both BILL & Gusto partner with JPM for example. This benefits both parties as the data fees become on-us and the Fintech benefits from bank distribution — which reduces a major cost

What is the impact of data use limitations?

Data use restrictions are a key difference between the two sides:

JPM’s position is consistent with both their current Aggregator contracts and Rule 1033: “… third parties should be restricted from using customers’ data for purposes beyond what the customer authorized …”

AFC is silent on the topic: “… any effort to restrict or monetize access to consumer-permissioned financial information is a direct threat to responsible innovation …”

The JPM position reflects compliance concerns, for example:

Banks can’t even using their own data for cross-sell if the consumer declines to allow it; but, once the data leaves the bank a Fintech or Aggregator might do exactly that with the data. This is a compliance concern

The more parties have access to the data without agreeing to accept liability, the more likely it is that banks will be left holding the bag in a breach. Banks have third-party oversight obligations which can’t be exercised if the data bounces from Fintech to Fintech after leaving the bank

Fintechs have proposed using bank data to build credit bureaus among other businesses. If the bank is supplying the data, even involuntarily, it could be subject to FCRA regulation, which is onerous

And those are just the concerns from when I was involved.

The AFC position decries the monetization of consumer data, unless of course it is monetized by the AFC member – in which case it counts as “responsible innovation”. I am being snarky here, but it is based on experience.

The basic issue is how permission is granted. I have seen many examples of lawyerly permissions that effectively permit the Fintech to do whatever they want with the data. Even with Rule 1033, which banned secondary usage, I spoke with Fintechs who thought they found loopholes so they could monetize the data any way they wanted.

The data is valuable and smart business people will find uses for valuable data unless restricted by law or contract. I would hope the AFC statement overlooked this topic rather than deliberately ignoring it to free Fintech’s from any data use restrictions.

My vote would be for plain English, prominent disclosures that identify what data is taken and what it will be used for — without lawyerly loopholes. JPM says much the same thing: “…the customer should know exactly what data is shared and when and how it is used.”. Rule 1033 agreed.

Conclusions

The big question that can’t be answered yet is how material these fees really are. If they are modest – similar at scale to ACH fees or IC+ merchant acquiring fees, they will not disrupt Fintech economics materially and will incent the banks to invest in their API infrastructure. In particular, smaller banks might see a reason to join API programs rather than be screen scraped – that might save the Aggregators a lot of work on 30% of consumers’ data.

It is also possible that big Aggregators absorb at least some of the cost as they have a scale advantage over smaller Aggregators. JPM’s rumored tiered pricing schedule gives the big Aggregators an inherent advantage – the big will just get bigger. Whatever share of the fees that Aggregators absorb is that much less that the end Fintechs need to cover.

Clearly some use cases, like PFM & Small Business GL, are disproportionately impacted by transaction fees. I would expect the banks to come up with more affordable solutions for these use cases — in particular, the two-tier, speed-based pricing that Fintechs pioneered.

The apoplectic response of the AFC seems overdone given that Fintechs already buy all kinds of data today and this would be a modest cost layer for particularly high quality information. The end-Fintechs might also optimize their usage once it becomes more expensive, say, taking say 6 months of data instead of 12. Or taking advantage of two-tier pricing to shift access times.

Aggregators have been charging Fintechs for years without a peep from the AFC. I have spoken to many Fintechs who complain about Aggregator fees, but I have never seen an AFC press release complaining about them!

Finally, banks themselves are big users of aggregation — for the same reasons that Fintechs use them. If banks universally impose fees, they will also be paying them.

I agree. "Write access", which they call PISP over there would change a lot, but the banks would furiously resist. One often overlooked difference between there and here is that PISP is only permitted for certain regulated intermediaries. Not every end fintech can do it for themselves. There are special purpose charters required to get PISP permission.

If we followed the same pattern, you would have to have a "Fintech Charter" for the aggregators and bigger Fintechs (like PayPal & Stripe) that wanted to do this for their customers. Those licenses would come with all kinds of rules that the intermediaries might not like so much

Ryan -- thanks for the input. While their language is confusing, the JPM fees don't actually seem to touch the actual payments (generally ACH). They might impact the balance check that some A2A providers do before submitting the ACH Debit. The aggregators already charge for the balance check, so whatever JPM adds will be on top of those fees. I suspect that aggregators can simply avoid the balance checks as they learn more about their customers -- a high-balance DDA may never need a balance check while a low-balance DDA always will. Again, it comes down to how much JPM charges and how well Fintech's can use risk modeling to reduce their volumes.

As I understand it, the bulk of Open Banking today is for either Identity checking or to grab the account number. The third biggest is balance checks. So I agree, it is more to reduce onboarding friction at Fintech's than any real product innovation.