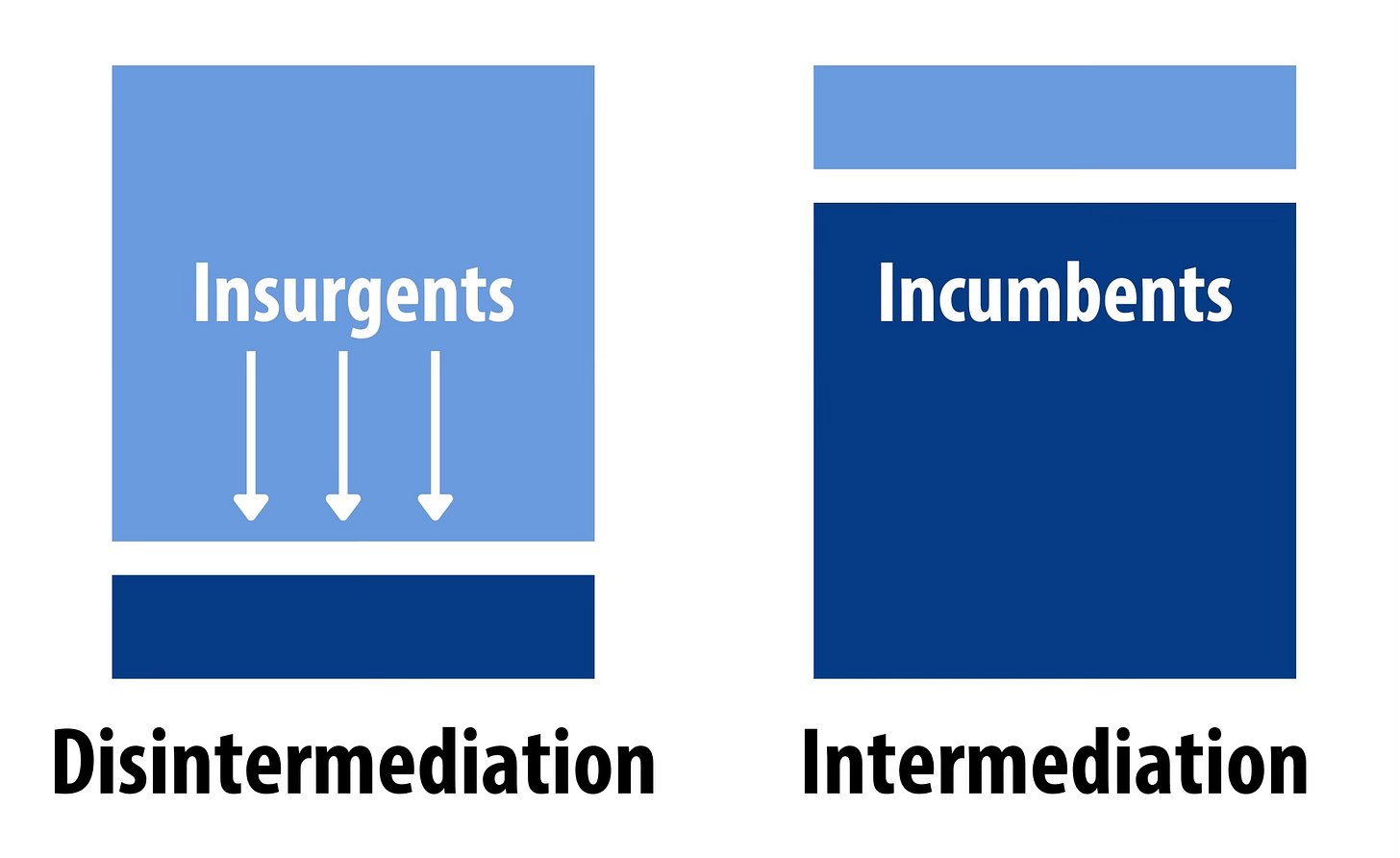

Disintermediation versus Intermediation

Disintermediation is a useful concept whose meaning has been diluted by imprecise usage. The Fintech challenge is really about "intermediation"

The technical definition of disintermediation is: The removal of intermediaries from a supply chain, or "cutting out the middlemen" … (Wikipedia).

In banking, disintermediation has a narrower meaning: the removal of Banks (“financial intermediaries”) from a class of financial transactions. For example, the migration of savings from bank accounts to money market funds is an example of bank disintermediation; or, corporations financing via commercial paper rather than bank loans. Here, the underlying financial instrument, the related transactions, and the customer engagement all leave the banking industry. Hence, disintermediation.

However, the term is often applied to cases where a Fintech inserts itself between the end customer and the bank, while the transactions or balances remain with a bank. I call this “intermediation” as the Fintech is adding a step in the value chain rather than removing one. Fintechs often start with an intermediation model but plan to disintermediate banks as an end-state. Although that end-state rarely comes to pass, intermediation can still be a serious threat.

A good example is P2P. In the early 2010s, Venmo, Cash App, Facebook and other tech firms launched P2P services. They saw P2P as a way to grab digital engagement that could be leveraged in other ways. The big banks also launched P2P services, however, the Fintech P2P services had the illusion of real time availability while bank services typically had delayed availability (via ACH). The biggest banks offered real time availability for on-us transactions, but on-us was only a fraction of the total volume. Some banks charged for P2P while the Fintech services were always free.

Fintech P2P was growing at triple-digit rates and was particularly popular among the youngest demographics – who used the services several times per week. All users of Venmo still had a primary checking account to fund their P2P usage, so there was minimal disintermediation. And many users of Cash App had no bank account to begin with so that service also demonstrated minimal disintermediation. Facebook’s service moved funds from the senders DDA to the receivers, so zero disintermediation.

Without digital P2P, most use cases would have used cash so there wasn’t even a shift of transactions away from cards. The Facebook service even used Visa Direct & MasterCard Send to move the money, so they actually earned money for the banks. In other words, the banks lost no revenue to Fintech P2P and the vast bulk of balances stayed within their walls.

So why was this threatening to banks? The banks were investing billions in mobile apps and web sites but digital engagement was still nascent. Further, some P2P services used a stored-value model that was taking a small share of balances from the primary DDA (usually well under $200) – but perhaps the start of a larger outflow.

More threatening was that P2P Fintechs were publicly discussing expansion into other financial services. Venmo ultimately did add debit and credit cards and Cash App added debit cards, stock trading and savings accounts. Venmo evolved Pay-with-Venmo for commerce, like parent PayPal; Pay-with-Venmo competed with cards when the consumer paid with their stored balance or funded via ACH; Cash App also has commerce functionality within the Block Seller ecosystem.

So while the immediate threat was intermediation (i.e., loss of digital engagement), the longer term threat was disintermediation (i.e., shifting balances to the Fintechs). The banks formed Zelle to anchor digital engagement onto their own mobile apps and web sites. They never charged either consumers or merchants for the service.

Zelle offered two advantages over Fintech P2P: 1) Real time funds availability into a customer’s primary DDA rather than a stored value account 2) Convenience, by executing P2P through the bank’s app, which was already on a customer’s mobile. This value proposition resonated with consumers and Zelle today is bigger than all competition combined (by value) and growing faster off that higher base.

An example with a somewhat different outcome is Apple Pay. At inception, Apple Pay was only a form factor that transferred tokenized card numbers to the merchant securely via the NFC standard – a Card industry standard, that wasn’t promoted much in the US. All Apple Pay transactions still occurred on a credit or debit card – so, NO disintermediation, but obvious intermediation.

In this case banks did not club together as in Zelle, but instead allowed Apple to capture the digital engagement. For this service, Apple charged issuers 15bp on credit cards and half a penny on debit cards. By controlling the UX, Apple was able to extract economic value from the issuers without disintermediating anything.

Over time Apple leveraged that digital engagement to launch branded financial products like credit cards, savings, installment loans, & P2P. Almost all of these are delivered via bank partnerships rather than by Apple itself – so these products shift share among banks, but it did not disintermediate the banking industry. The Apple Card took Goldman from nothing to the 10th biggest card issuer in less than 5 years, but Goldman is a bank that holds the balances and processes the transactions. Similarly, Apple Pay Cash (P2P) partnered with GreenDot Bank.

White labeling bank products is not unusual in big tech as Amazon has done much the same with its Card products. But there is almost always a bank charter involved so the industry has not been disintermediated, but rather cannibalized by other banks issuers (i.e., Chase, American Express, Synchrony). Uniquely,

So the danger of intermediation is real: Fintechs can use digital engagement to launch their own financial products or they can capture revenue from the banks that provide the financial services. Amazon extracts most of the spend-based profit from its cobrand cards while leaving most of the credit revenue and associated risk with its issuers. Apple taxes issuers for using the Apple Pay channel. Both Apple & Amazon seem happy with these arrangements without moving to disintermediation.

The banking industry is not blind to this. Early Warning (the consortium behind Zelle) is launching the Paze digital wallet to replicate Zelle’s P2P model in Commerce. Page has a few wrinkles that only banks can deliver and the aim is the same as Zelle – recapturing some of the digital engagement that now uses Apple Pay or PayPal.

So what should the playbook be for the banking industry against intermediation threats? A few tactics have track records:

Resist tech company dominance in the first place. The banks supported Apple Pay in its early days when they could have resisted. One tactic would have been to put NFC chips into all cards, providing customers with a way to tap-and-go without using their phone. This was common in Europe and Canada pre-Apple Pay. But US banks didn’t follow because the cost to reissue all those cards was too high while NFC earned no extra revenue. Solving the POS problem with NFC Cards might have given the banks more negotiating leverage on the fees.

Domesticate the threat. Another success story was how banks dealt with data aggregators like Plaid, Finicity, MX and others. At inception the aggregators were screen scarping data from banks and using that customer data for their own purposes. They also collected customers’ log-in credentials, creating cyber risk for the banks. And finally, they accessed the banks very frequently – taxing server capacity. At first the banks tried to block access, but the aggregators always got around those tactics.

Eventually, detente emerged. The bigger banks provided API access while surrounding that API with contractual protections. For example, the aggregators couldn’t store login credentials, but instead would get a token tagged to them only. They couldn’t use the data for anything other than the specific purpose they collected it for. And they had to delete the data after that purpose was fulfilled. Aggregators could move data from banks to Fintechs more easily, but most of the cyber and privacy risk was eliminated.

Pursue white label solutions rather than partnering under the Fintech brand. BofA and JPM have dealt with small businesses merchant acquiring by white labeling a third-party solution. These solutions are fully integrated into the banks’ digital small business suite. In contrast, most other large banks distribute Fiserv’s Clover. Here, Clover is the brand and Fiserv provides all the services – including financial services like merchant lending. Clover is a competitive solution whose brand carries weight with merchants, but it undermines bank distinctiveness as many competitors offer exactly the same product.

These approaches allowed banks to leverage their distribution advantage without big tech investments. In contrast, US Bank and PNC bought their own solutions: USB bought Talech while PNC bought Linga. These banks get the advantages and disadvantages of proprietary solutions: They can fully integrate with their owner banks, but the banks bear the full investment cost to maintain functional currency. The question is whether they can invest fast enough to keep pace with Clover, Square, Toast et al.?

Create industry utilities faster. Creating utilities is painful. Getting large banks to agree on priorities and funding is difficult when the target is digital engagement rather than a clear financial metric. Staying consistent with Antitrust law constrains tactics. Utilities can win, but there are as many failures as successes. Some examples:

Zelle has been a clear success. The biggest banks saw the threat from Fintech P2P, banded together in a small group, and built out a meaningful competitor with distinctive advantages. The banks entered the market early, before P2P had broken into mass market segments Nevertheless, it took over two years from inception to launch – lightning quick by bank standards but slow by fintech standards. In the end the banks’ inherent distribution and functionality advantages won out

TCH’s Secure Cloud was a missed opportunity. TCH identified the need for a tokenization utility well before the dawn of Apple Pay, however as a 24-bank consortium, it couldn’t move fast enough, so Apple Pay tokenization ended up with the card networks – where it works well, but cedes control to a publicly-traded entity. At the time, Visa announced it would monetize tokenization; but, industry outcry made them retreat. Had Secure Cloud gone faster, the it might have won the day

Akoya is a work in progress. Here, the banks were early to the game, and the consortium was smaller than TCH (14 vs. 24) albeit twice as big as EWS (14 vs. 7). Nevertheless, Akoya has not won the day so far. The largest banks resolved the key risk considerations via contracts rather than a competing utility and Open Banking regulation may address the key risk challenges without a utility

In summary, banks can win the Fintech intermediation challenge, but it requires acting early, decisively and often, collectively.

Key insights

The Fintech challenge is usually about intermediation, not disintermediation. Fintechs provide an experience layer between the bank and its customers that reduces digital engagement with the bank — but, the balances and transactions often stay with the bank

Fintech’s rely on partner banks for most of their financial products, so while the revenues and balances stay within the banking industry, those balances may shift from one bank to another. Goldman’s partnership with the Apple Card took share from other card issuers, but moved the balances to Goldman’s bank, not to Apple

Fintechs often plan to migrate from intermediation to disintermediation to increase their ARPU. This has a spotty track record; however, some Fintechs do extract revenue from the banks without offering proprietary financial services. These revenues include “taxes” (Apple Pay 15bp) and revenue sharing (Amazon’s credit cards).

Banks’ can successfully challenge intermediation if they start early enough and, often, if they act collectively. It is difficult to cost-justify such initiatives because the value of digital engagement is hard to measure and the odds of intermediation becoming disintermediation are hard to handicap.