Key insights in this post

Cobrands have been a staple of the card industry since the 1980s

Card issuers got differentiation that appealed to a defined set of consumers:

National brands recognized by consumers

A differentiated rewards currency

A defined customer base with a unique marketing channel

The partners won loyalty from their best customers and revenue sharing from the card issuers

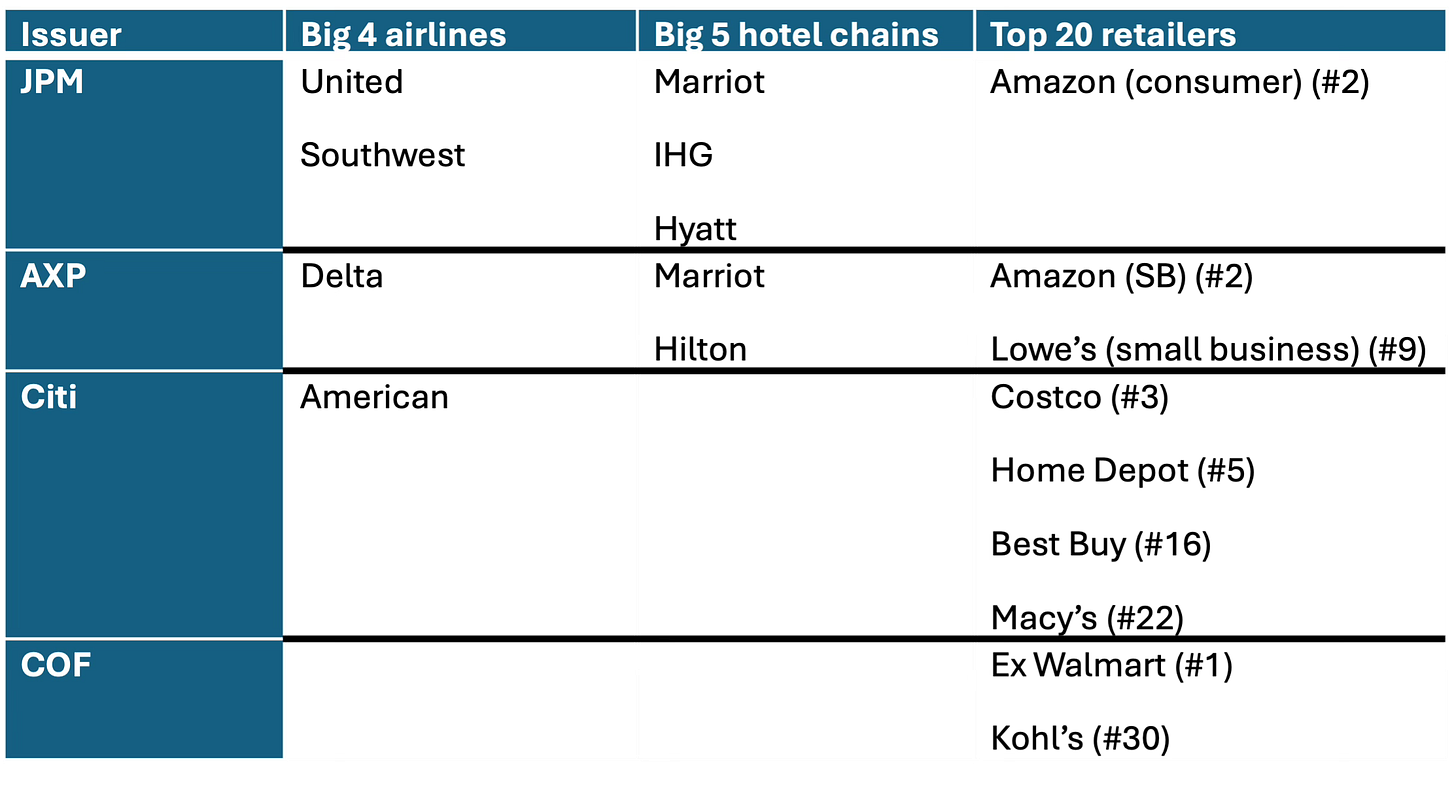

Both the card issuers and the partner side have substantially concentrated since those early days

We are down to 5 major issuers, only 4 of whom issue cobrands

We have only 9 major names in the T&E space: 4 airlines & 5 hotel chains

We have 5 major retailers that dominate cobrand cards due to the breadth of their merchandise and the frequency that consumers shop their offerings

Friction has emerged in these relationships

The partners have captured the bulk of spend economics, leaving the issuers dependent on lend economics

The T&E cobrands have lost appeal as most business travelers now must use corporate cards rather than personal cards

The issuers have super-premium products that capture the transactor segment under their own brands — without revenue sharing

The interchange that funds rewards is facing downward pressure from surcharging and network discounts

The Apple Card is trying to find a new issuer among a few leery issuers

Only 3 of the top 5 issuers appear fully committed to cobrands

All these issuers declined the Apple card originally

The Card proposition is inherently uneconomic from a lend, spend, and servicing perspective — and may also have unsustainable revenue share

New entrants like Goldman are unlikely, although Synchrony might make a run at it

Apple will likely have to make concessions to attract an issuer, for example,

Reform the lend proposition by tightening underwriting and allowing late fees

Take less revenue share

Perhaps, reduce rewards on the Apple Pay 2% in particular

Take servicing in-house or relax servicing requirements

Note to readers: I will be covering the Global Payments, WorldPay, FIS deal next week. I could not do it justice this week. To cut the suspense, I agree with most of the commentary I have read so far. My contribution will be more context on how the deal impacts Issuer Processing (TSYS + FIS) & Merchant Acquiring (GPN + Worldpay) overall.

Introduction

Cobrand credit cards date back to the 1980s. They include Affinity Cards, Airline & Hotel cards, & Retailer cards. The modern era may have kicked off with 1990’s AT&T Universal Card that offered calling minutes as a rewards currency. The launch coincided with telephone deregulation where the price of long-distance service was falling, but consumers still had a ration of minutes they managed to each month. The AT&T card gave free long-distance minutes in return for spending on the card. It was very popular, the Apple Card of its day.

Cobrand cards helped card issuers differentiate and helped the partners lock in loyalty. Issuers started a land rush to lock in the best partners. Over time, both the issuers and the partners consolidated so that today, it is giants serving giants. An arms race has ensued between the biggest issuers and biggest partners to see who grabs more economics.

Apple was the last new giant to hit the market and Apple Card growth was nothing short of spectacular. In under five years it made Goldman the 10th biggest card issuer, starting from zero. But Goldman lost billions on the Apple Card and recently announced it was exiting the deal early. Apple is searching for a new issuer to replace them.

In similar circumstances a few years earlier, Costco put its portfolio up for bid and set off a feeding frenzy which Citi & Visa subsequently won. The card world changed since then and enthusiasm is not as high for the Apple Card. This post will try to explain why.

Why was Cobrand so key for so long?

Cobrand solves problems for both the partner and the issuer.

Issuers

Card issuing has a differentiation problem. Every incumbent bank issues on Visa or MasterCard or both and benefits from their global acceptance and common rules; most banks use TSYS or Fiserv for processing; the networks set the interchange rates that fund rewards. Regulations standardize many other features. Issuers can differentiate on pricing, like APR & fees, but these differences are rarely compelling. American Express faces the same challenges despite controlling its infrastructure.

Cash Back commoditized rewards as the value of a dollar is transparent whereas points or miles programs are more opaque. Comparison sites like Credit Karma and PointsGuy emerged to highlight the value differences between cards.

Saturation compounds all this. Most creditworthy consumers already have one or more cards, so it takes real differentiation to get them to switch. That can be an upfront inducement like a signing bonus – which is expensive – or a unique rewards proposition – which is where cobrand comes in.

Cobrand provides both a differentiated rewards proposition and a more targeted origination channel:

Partners provide a “currency”, like frequent flyer miles, for unique rewards versus transparent cash-back. Typically, the currency will cost less than pure cash-back yet be highly valued by the end customer

Partners provide a marketing channel to a loyal customer base, so the issuer can tailor propositions to that base. In theory, the cost of acquiring those accounts should be lower. If the partner skews to certain segments, the propositions can be even more targeted and efficient. For example, T&E brands, skew affluent. One early cobrand was the AFL-CIO card whose cardholders were prime revolvers

When cobrands emerged, the banking industry was still faced interstate banking restrictions. Bank brands were local or regional. Cobrands gave the issuers a national stage to grow scale beyond their regional roots. The alternative was spending a mint on direct advertising and direct mail to create a national brand – like Amex or Discover.

To summarize, cobrands gave issuers:

National brands recognized by consumers

A differentiated rewards currency

A defined customer base with a unique marketing channel

The issuers that went heavily into cobrand built scale beyond their regional base.

Partners

Partners value cobrands to generate revenue and to anchor loyalty from their best customers. Cobrand revenues go beyond just a revenue share:

An upfront signing bonus, sometimes from both the issuer and the network

An ongoing revenue share, usually based on bps of spend

Bounties for new originations

Currency purchases, for miles/points, which may be free or low cost to the partner

The cobrand anchors the partner’s best customers. The partner also gets a new marketing channel via the monthly statement and other card channels.

Friction points

While cobrands can be win-win, there is always friction between the partner and the issuer:

Underwriting standards. The partner wants to approve as many customers as possible, but they don’t share in credit losses. The issuer needs to manage credit losses to make a return

Marketing spend. Each side makes money in different ways. To the partner, virtually everything is upside while to the issuers, the cost to acquire a card governs marketing spend. The parties often disagree on how much to spend on marketing

Cross-Marketing. Many partners have contractual control over cross-marketing to cardholders. The issuers may face constraints on data sharing due to privacy regulations

Servicing standards. Every partner thinks their customers should get white glove treatment although the costs for this come from the issuer side. In some cases, the agreement specifies dedicated call center teams. Every exception to standard servicing reduces the issuer’s scale benefits

Generally, the bigger the cobrand, the more partner-weighted the terms.

What has changed

The biggest driver of change is concentration on both the partner side and the issuer side. Economic cycles then trigger shifts in the balance of power. Peculiar to T&E cobrands, a change in the use of corporate cards has reduced demand.

Mandated use of Corporate Cards

I was a consultant for several decades. In the early years, we all had personal airline or hotel cobrand cards to pay for our business expenses. The rewards supplemented the miles/points we got from actual travel. In my case, it was a Citi AAdvantage Card. We all paid for our leisure travel with those miles, as a perk of the job. At one point the Starwoods card became almost as ubiquitous among consultants as Tumi Luggage, HP 12c calculators, MBAs … and arrogance.

This ended around the Great Recession. All the major professional services firms adopted corporate cards and started mandating their use. Corporate cards paid a rebate to the sponsoring firm but only mediocre rewards to the staff. They were also used to enforce travel policies that limited some of the routing tricks that maximized miles accrual.

The staff threw a fit. Consultants threatened to quit. Petitions were launched. To no avail. Today company-issued corporate cards are mandatory and strictly enforced. This drained much of the spend volume from personal T&E cobrands. I dropped my AA card and replaced it with a cash-back card.

Without business travel spend, it became harder to accrue enough miles to fund personal travel. It didn’t help that the airlines kept devaluing points, adding expiration dates, imposing blackout periods, and restricting inventory. Then the pandemic hit and all travel screeched to a halt. T&E cobrands lost value.

I am sure some companies still allow personal cards for business travel. But corporate travel is concentrated in bigger professional services firms and a few other verticals – and the bulk of those firms mandate corporate cards.

With the T&E cards less dominant, cobrand emphasis shifted to mega retailers.

Concentration of issuers and partners

5 issuers now account for 80%+ of card spend. Of the 5, Bank of America doesn’t seek new cobrands and Capital One may be losing enthusiasm after its Walmart experience. That leaves JPM, Amex, and Citi as the major cobrand issuers.

A few smaller issuers pursue smaller cobrands, usually as part of a Private Label Credit Card business. These include Synchrony, Bread, TD & Wells Fargo. Barclays is a cobrand specialist and issues the Jet Blue card, which it famously lured from Amex, but they are small. Synchrony is the biggest of these and notably issues PayPal cards and Sam’s Club cards. It is rumored to be in the running for both the Apple Card and the Walmart card.

Virtually all major cobrands are now concentrated in four issuers: JPM, Amex, Capital One, & Citi:

A few retailers, have other arrangements:

Target (#7) & Nordstrom (#34) service their cards in-house, although TD is the issuer of record and controls underwriting and funding

WalMart (#1) is leaving Capital One for parts unknown – it may follow Target and service in-house via its Walmart One Fintech subsidiary or go back to Synchrony

Apple (#11) is similarly in flux as it picks a partner post-Goldman

The un-partnered top 20 retailers are in undesirable cobrand verticals, such as Supermarkets, Drug Stores, and Fueling. A few of these do have cobrands, but they are not particularly big programs.

The so-called “retail apocalypse”, triggered by the shift to eCommerce and the Pandemic, accelerated concentration as many large retailers of yesteryear went out of business. Many newer retailers are specialists and don’t have a scale cobrand program. Those that do, find a home at the PLCC specialists like Synchrony and Bread.

So, we may be down to three big cobrand issuers, with ~20 scale partners split among them. If Synchrony gets Walmart and/or Apple, it could become the fourth.

It is worth exploring why Bank of America and Capital One can remain top 5 issuers without the scale from big Cobrands:

Bank of America is relationship-oriented and largely markets cards to depositors:

It leverages captive channels to keep acquisition costs down

It has a bank-wide, multi-product rewards program to anchor relationships

It has a cautious credit policy

Capital One is a consumer credit specialist that has invested to establish a national brand, akin to American Express & Discover

It specializes in credit & marketing analytics that gives it efficient customer acquisition even without cobrand channels

It has a broad product portfolio to target different propositions to narrow niches

Discover will give it a second national brand to differentiate by segment and a closed loop network that gives it more freedom to innovate

American Express may not be retreating per se, but may have focused on small business programs. They lack a major retail partner after losing Costco, but are rumored to be in the running for Apple. Their T&E cobrands face the same pressures as all T&E cobrands. They do have small business programs at Amazon & Lowe’s, which is smart given Amex’s overall strength in small business cards. It is not clear if this is a deliberate strategy or a coincidence

Tension in T&E cobrands

The big issuers are to a degree hostage to the big partners. For example, Amex lost ~10% of its volume when it lost Costco and JetBlue. Cobrand economics deteriorated as the partners exercised their power. Critics started talking about a “winner’s curse”, such as when Citi won Costco, Goldman won Apple, Capital One won Walmart, etc.

Spend economics on T&E cobrands dropped below hurdle rates, making profits dependent on lending. The issuers were able to rebalance economics somewhat during the pandemic, but the price was bailing out their T&E partners … again. Those cards have reached the point where interests no longer fully align.

One issuer tactic was to focus their cobrand marketing on revolvers. The T&E partners want the high-spending transactors, but that segment no longer makes economic sense for the issuer. Instead, the issuer focuses contractual marketing spend on revolvers – where they still make money. This creates partnership tension.

But even more disruptive is the emergence of issuer-branded, super-premium cards. These have generous rewards allowing transactors to fund their leisure travel, but on any airline or at any hotel. Amex has Platinum, Chase has Sapphire, Capital One has VentureX, and Citi has Strata. Because the issuers don’t share revenue with Partners, they can enhance the consumer proposition and still earn a margin on spend.

To make them even more attractive, issuers are adding their own lounges in major airports and offering travel portals to deploy redeemed points. These cards lure high-spenders away from T&E cobrands while delivering better returns for the issuer. The T&E partners are not happy but have nowhere to go.

Changing power balance in the mega-retailer space

Balance of power faces a similar issue in the retailer vertical. Amazon, Walmart, Target, Costco, and Apple are the biggest names, and all have high rewards propositions:

Rewards consume more than the interchange earned for most on-us transactions. This is a particular challenge at these retailers as all of them have “VPP/MPP” deals with the networks that reduce their interchange to begin with. So the issuers are giving far more than they are getting. This only balances out if consumers use the cards for off-us spend at 1% venues. Unfortunately for issuers, some consumers optimize this structure. They use the cards for on-us spend but do off-us spend on a different card. That makes spend economics very negative.

The only way to remediate this is with lots of revolve – which is where these cards shine. They are used by a true cross-section of America which includes lots of prime revolvers. This is a major difference from the T&E cards favored by transactors. Retailer cards can be profitable if enough cardholders revolve responsibly.

At least they can so long as the revenue sharing is balanced. However, feeding frenzies meant that the revenue sharing often was too high to meet hurdle rates without a lot of wishful thinking.

Target alone gets around this. TD is the issuer of record, but Target handles the servicing. Walmart may be going in this direction by bringing the program under their Fintech subsidiary, Walmart One. Apple publicly toyed with the idea of in-house as well, but now seems committed to another partnership.

Amazon recently renewed with Chase under unknown terms, but presumably has managed to extract the maximum economic leverage with the minimum internal investment. There was public speculation that they even got a share of revolve revenue, but that may or may not be true. The Costco/Citi deal is approaching its 10-year anniversary and may also be up from renewal.

So here is today’s state of play among the big 5 programs:

Apple & Walmart are up for grabs

Amazon recently renewed (consumer card)

Costco is approaching renewal

Target is partially in-house

So where does the ecosystem go from here?

Threats to the Cobrand status quo

A few evident trends could upset this apple cart (pun intended).

Issuers retreat from Cobrand

More issuers may retreat from cobrand as Bank of America did long ago and Capital One may be doing now. TD and Synchrony seem to be the only issuers of size that aspire to step into the breach, but neither have the resources of the big 5. If the main playing field is JPM, AXP, & C, it is harder to set off a feeding frenzy. If American Express really has decided to focus solely on small business cards, we are down to two.

Threats to interchange

Merchants and regulators continue to pressure interchange. The Credit Card Competition Act (CCCA) has been reintroduced as one example. The Merchant Settlement still looms, which could directly reduce interchange and eliminate Honor All Cards to allow differential surcharging and acceptance.

This would impact T&E cobrands more than Retail cobrands as they depend more on high-spending transactors. The Retail cards all have a low off-us rewards rate that would still be affordable with somewhat lower interchange rates. On-us is already uneconomic.

Surcharging

If the merchant settlement limits Honor All Cards, merchants could start differentially surcharging high-cost cards. We have already seen the broad expansion of “dumb” surcharging at small merchants – where every card gets the same surcharge. Imagine a world where cards get a surcharge proportionate to their interchange. In that environment, consumers are paying for their own rewards and might retreat from high interchange cards entirely.

And then there’s Apple Card

Apple Card may be the last hurrah for the cobrand market. The card introduced features that made it economically unattractive to issuers. All major issuers showed unusual discipline in declining to partner on those terms. Apple’s good fortune was finding the new entrant, Goldman, that wanted a way into credit card at any cost.

The program was embraced by consumers and likely lucrative for Apple, but a financial disaster for Goldman. In five years, Goldman went from zero to the 10th biggest US issuer … and lost a fortune along the way.

The rewards proposition itself was not the issue. The 3/2/1 structure was comparable to Amazon, Costco, Walmart, Target, etc.; although, the rising popularity of Apple Pay at 2x cash-back locked in a growing rewards cost for off-us transactions, i.e., less at 1%. Being able to market through the Apple Pay channel generated lots of cards at low CAC.

Credit terms were a key issue. In its zeal to be consumer friendly, Apple insisted on looser underwriting standards, lower APRs and no late fees – attracting low-FICO customers and raising credit losses. Apple also mandated servicing standards that raised costs. Goldman recently cried “uncle”.

Apple now needs to find a new issuer from among the small group that turned them down the first time – and whose skepticism was proven correct. That leaves a few options:

Change those features that make the card unprofitable, particularly on lending. That would reduce consumer value but keep Apple & the issuer whole

Keep most of the consumer terms, but keep the issuer whole by reducing Apple revenue share. Apple would still have a loyalty benefit from on-us rewards. This option still requires adjusting the credit terms

Follow the Target route to sustain servicing standards while outsourcing the credit-related functions to a bank. This would still require tighter underwriting and impose late fees, but preserve other aspects of consumer experience.

Something has to give. The remaining cobrand issuers already have mega cobrands that are under hurdle and won’t enthusiastically take another. The current economic environment does not lend itself to wishful thinking. Further, top cobrand issuers have their own super-premium cards and national brands – they may view the Apple Card as cannibalizing their own cards for no economic benefit. They can afford to say no.

Synchrony is rumored to be in the running and could see an upside. They have no branded cards to cannibalize and no brand at all. They have experience dealing with mega-issuers like Walmart. The Apple Card would be a growth engine where many of their smaller retailer programs are stagnant.

However, Synchrony said goodbye to Walmart once to preserve economics and are unlikely and unable to subsidize Apple. They are disadvantaged on funding costs given the lack of a branch network to raise DDA. They are a pure-play lender that can’t offset credit losses from elsewhere in their business. They can’t say yes with an open checkbook.

They may even be in the running to win back the Walmart card to go with their Sam’s Club program. Along with their PayPal programs that may solve for growth without Apple.

Apple has historically been a master at herding banks. It got them to pay 15bp to have their cards in Apple Pay. But that happened before the card industry was so concentrated. It is harder to herd a handful of whales than a long tail of minnows.

Conclusion

We are long past peak cobrand. Chase & Amex both have policies that limit new cobrands to those with compatible brands, large customer bases, and an attractive rewards currency. Few programs meet that hurdle. Bank of America is above the cobrand fray and Capital One may be retreating. Citi & Synchrony will deal with Tier II retailers but mix PLCC cards with cobrand to get more lend revenue. Feeding frenzies may be a thing of the past.

On the partner side, the T&E brands have limited leverage. Demand for their cards is not coming back to historical levels.

Only the mega-retailers still have leverage, but Costco, Walmart & Apple defected for better economics Amazon may now have extracted the maximum possible value from Chase. It is clear the partners have no loyalty to the issuers, so reciprocal loyalty is unlikely. It may be that we go back to the future and all these programs follow the Target path of insourcing a good part of the offering. The retailers would still need banks as lending partners, but may do everything else themselves and use cards more freely as a merchandising tactic.